Part 2

Content Warning: this essay contains descriptions and discussions of assault and rape.

[The presiding devil] might make love to her and have carnal knowledge of her: to whom he said maliciously that he would lay her down on the ground supporting herself on her two hands and feet, and that he could not have intercourse with her in any other positions; and that was the way the presiding devil enjoyed her, because at the first sensation by the neophyte of the member of the the presiding devil, very often it appeared cold and soft, as very frequently the whole body.

-Quellen tract (1460) describing Arras witches and Sabbat

Previously, I briefly discussed the context in which demon copulation occurred as well as traced the approximate timeline alongside the fervency of witchcraft theory in Europe during the Middle Ages. If you missed that blog post, you can read it here.

Now, however, in part two the study is going to focus on the specificities of the accused’s confessions. In this blog post, I’m going to be looking at how the physical bodies of the demons and devils were described, including their genitalia, as well as how sex was described.

Prior to 1570

Because witchcraft theory, and thus demon copulation and the way it was portrayed, encountered a shift around 1570 due to a second wind of an even more fervent push against skepticism, the physical descriptions of demons and devils reflects this shift as well. Prior to 1520, and as early as the 1100s, demons were described as handsome and overtly beautiful. Merlin’s mother testifies to this in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain in which she describes the mysterious incubus who visited

her routinely in her chamber at night as “someone resembling a handsome young man” who “often made love [to her] in the form of a man”.2 It’s crucial to note here that Merlin’s mother does not state that she was visited by a man but rather something that resembled a man, indicating that she knew it was not human despite its beautiful disguise.

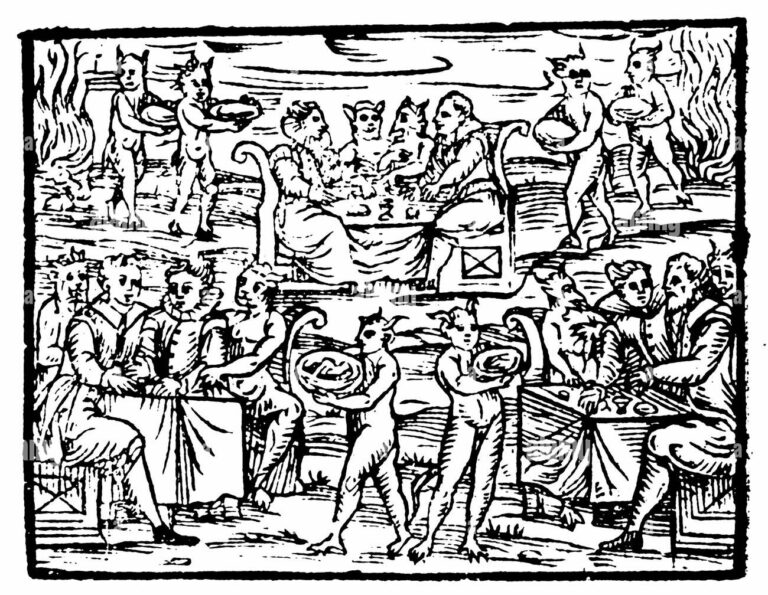

Devil Seducing Witch, Konstanz ([1489?])

The 1523 theatrical book, Strix, sive de ludificatione daemonum or The Witch; or, On the Illusions of Demons, written by Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola, was based off of a witch trial that Pico had participated in. In the book, Strix, an accused witch, is being questioned and interrogated about her sexual encounter with a demon by three men. She tells the men that her demon lover, Ludovicus, had appeared in every sense as a normal man except for one small detail: his feet. They were those of a goose and reversed, so they pointed backwards.3 One such interrogator, Dicastes, explains the reason for this is because while the Devil can nearly create a “perfect facsimile of the human body” he can never truly get the feet right as God purposefully makes them come out inversos et praeposteros so that people are not fooled in the presence of demons and devils.4 When asked if Ludovicus had shown Strix any other kind of feet besides gooselike, Strix replies, “Never any other” and that he “Never [appeared] in any form but human if he intended to copulate with me”.5 The reality of this framing positions the accused as automatically guilty of sinning, as they have no excuse for knowing they had sex with unholy corporeal beings with such a dead giveaway.

The 1523 theatrical book, Strix, sive de ludificatione daemonum or The Witch; or, On the Illusions of Demons, written by Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola, was based off of a witch trial that Pico had participated in. In the book, Strix, an accused witch, is being questioned and interrogated about her sexual encounter with a demon by three men. She tells the men that her demon lover, Ludovicus, had appeared in every sense as a normal man except for one small detail: his feet. They were those of a goose and reversed, so they pointed backwards.3 One such interrogator, Dicastes, explains the reason for this is because while the Devil can nearly create a “perfect facsimile of the human body” he can never truly get the feet right as God purposefully makes them come out inversos et praeposteros so that people are not fooled in the presence of demons and devils.4 When asked if Ludovicus had shown Strix any other kind of feet besides gooselike, Strix replies, “Never any other” and that he “Never [appeared] in any form but human if he intended to copulate with me”.5 The reality of this framing positions the accused as automatically guilty of sinning, as they have no excuse for knowing they had sex with unholy corporeal beings with such a dead giveaway.

A similar confession took place in Germany in 1587, in which a licensed midwife named Walpurga Hausmännin, confessed to not only maleficia—harmful magic—but demonolatry, or sexual relations with demons. 31-years before her trial in 1556, Walpurga engaged in a one-night stand romp with a fellow worker.6 However, after having sex, Walpurga began to notice terrifying peculiarities about her lover Bis im Pfarrhof that pointed to him not being human at all, but the Devil: his feet were cloven hooves and one of his hands appeared “as if made of wood”.7 Walpurga realized with horror what she had done, however, this did not prevent her later the next night from having sex with the Devil yet again when he returned in the same form, and then later yet embarking on “a contiguous orgy of sexual excess” with the Devil.8

For devils can assume the bodies of dead men, or re-create for themselves out of air and other elements a palpable body like that of flesh, and to these they can impart motion and heat at their will. They can therefore create the appearance of sex which they do not naturally have, and abuse men in a feminine form and women in a masculine form, and lie on top of women or lie under men; and they can also produce semen which they have brought from elsewhere, and imitate the natural ejaculation of it.12

When servicing women, devils and demons initially were described as well-endowed, though not all. Henry Boguet—a well known jurist and judge in the County of Burgundy as well as a famous demonologist who wrote a Discours exécrable des Sorciers (reprinted 12 times in 20 years!)—joked that none of the witches in France-Comte had “seen [a demon’s/devil’s penis] longer than a finger and correspondingly thin” and that Satan served other counties better than he did the French-Comte.13

A 17 year old witness examined by De Lancre testified that the devil always had a member “like a mule’s, having chosen to imitate that animal as best endowed by nature; that it was as long and as thick as an arm…and that he always exposed his instrument, of such beautiful shape and measurements”14. The girl had confessed further that not only did the devil have a member like a mule’s, but that he had “appeared as both man or goat”.15 This anthropomorphic form was yet another common description of demons and devils, however, it especially became more frequent in 1570 when witch theory and witch trials not only recommenced, but did so when demon relation confessions began to become more violent and sensationalist, removing itself from the idea that the act was pleasurable for the accused.

In the case of the character Strix, from Pico’s Strix, when the interrogators questioned how a demon could even copulate if they have “neither bones nor flesh” Strix supplied that “the parts put on by them are similar to flesh and bones, but bigger than those of any mortal” and that their parts were “softer and very similar to flax or cottonwool that has been bundled and densely packed”.16 This did not interfere with Strix’s pleasure while having sex with the demon—a pleasure like no other on earth—and one of the interrogators surmised that this was due to the demon’s presenting themselves as beautiful, well-endowed, good lovers, and that they pretended to be in love with the witches.17

Early accounts, especially those prior to 1520, described the intense pleasure of diabolic intercourse as an act that left people physically exhausted for days. In 1458, for example, Inquisitor Nicholas Jacquier explained that demonic copulation was “inordinate carnaliter [inordinately carnal]”, and that many witches “for several days afterwards remain work out [afflicti et debiliatai]”.18 Other accounts in Italy further confirmed this, such as Grillandus, the famous papal lawyer, who reported that women confessed they enjoyed sexual relations with the devil ‘maxima cum voluptate [with great pleasure]”.19 In fact, exhaustion (accused to have been brought about from sexual activities with demons and devils) in early witchcraft theory treaties was a preliminary sign of demonolatry by many theorists including Jacquier. According to Stephens, Jacquier

claimed to have interviewed the servants of those who fornicated with demons, who testified that they often found their masters and mistresses bedridden and exhausted on Friday. Some even stayed abed several days thereafter…It became clear…that the cause was sexual overindulgence at the Sabbat, which is always held on Thursday night.20

Sexual satisfaction and pleasure was such a key point when describing demon copulation that theorists like Girolamo Visconti, a Milanese Dominican who wrote two witchcraft theory treaties in 1460, described how witches enticed newcomers into their sect by describing the sexual pleasures that awaited them at the Sabbat. According to Visconti, female witches lured women to the “witches’ game” with the promise of handsome young men, and male witches with the promise of beautiful women. Both men and women would find “every kind of pleasure and sensuality that one can enjoy” while at the Sabbat, especially because every person was assigned their own personal sex demon “with whom they have sexual intercourse, and who appears to them often, both in the home and outside it, when they are wide awake, as they themselves affirm”.21 Sounds oh so dreadful, doesn’t it?

After 1520

Descriptions of bestial demon copulation increasingly became more commonplace. Authorities like Carpzov (1635) and Pott (1689) remarked that the devil’s form appeared as animal or bird, specifically serpents, goats, or ravens, though their animal forms did not inhibit demons and devils from copulation. “Before they were burned, the Scottish witches at Borrowstones in 1679 testified to the commissioners how the devil ‘would have carnal dealing with [them] in the shape of a deer, or in any other shape, now and then. Sometimes he would be like a stork, a bull, a deer, a roe, or a dog, and have dealing with [them]’.31

In Boguet’s Discours des sorciers, Boguet believed that the devil frequently assumed the shape of a dog to abuse women32, while in De Lacre’s Tableau (1612), witness Johannes d’Aguerre swore:

The devil in the form of a goat, having his member in the rear, had intercourse with women by joggling and shoving that thing against their belly. Marier de Marigrane, aged fifteen years, a resident of Biarritz, affirmed that she had often seen the devil couple with a multitude of women, whom she knew by name and surname, and that it was the devil’s custom to have intercourse with the beautiful women from the front, and with the ugly from the rear.33

Painful demon copulation testimonies, as well as witchcraft theory, would persist until the end of the 17th century, in which case much of Europe “had lost their certainty about the prevalence, if not the potency, of maleficium; the danger, if not the existence, of a diabolical conspiracy; and the practicality, if not the possibility, of identifying and punishing those involved in either pursuit”.34 By the 1700s, witchcraft theory was largely dismissed and the devil transformed into a being of “at most a moral influence and possibly a complete fiction” and those who clung to the idea that demons or devils were physically real were thought to be fools or mentally unwell.35 This did not mean that testimonies of maleficium or demonolatry disappeared outright. Vigilante actions against accused witches took place in the 19th and 20th centuries, however, the “virtual cessation of legal actions against witches by the end of the eighteenth century confirmed the profound change that Europe had begun to undergo in the previous century”.36

In the case of Henry Fuseli, the Swiss painter behind The Nightmare (1781) (as seen above), though witchcraft theory was not explicitly present in the suggestive oil painting, the grotesque demon perched upon the chest of the sleeping, voluptuous woman echoes remnants of a not so far gone era of demonolatry. Though Fuseli never remarked on the symbolism of the piece, the painting is rich with erotic iconography, from the woman’s swooning, full-form to the imp or incubus sat on her chest. In fact, many art historians interpreted the painting to be representative of sublimated sexual instincts, with the incubus standing to represent the male libido and the intrusive horse head peeking through the curtain representing sex itself.37,38 Marcia Allentuck in Woman as Sex Object (1972) even argues that the painting’s intent was to portray the female orgasm. Fuseli would not only create multiple versions of this painting, but produce yet another painting concerning the subject of incubi and women in 1794 titled “The Incubus Leaving Two Sleeping Women” (seen below).

Striking artistic similarities would find themselves duplicated in other artist’s work like Austrian Vincenz Georg Kininger’s “Incubus” (1795) (below), indicating the influence not only of demonolatry, but of Fuseli as well.

Works Cited

- Walter, Stephens. Demon Lovers: Sex, Witchcraft, and the Crisis of Belief. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2002. pg. 37.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, ed. Michael D. Reeve, trans. Neil Wright (Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press, 2007), Book VI, 11. 531-40.

-

Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola, Strix, sive de ludificatione daemonum, sigs. D2v; Pico/Alberti, 109.

-

Stephens, Demon Lovers, 95.

-

Pico/Alberti, Strix, 112.

-

“Urteil…,”103-109. Translated in “Judgment on the Witch Walpurga Hausmännin.” Reprinted in Monster, ed., 75-76

-

“Urteil…,” 103-4; Monter, ed., 76.

-

Ibid.

-

Rossell Hope Robbins, The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. New York: Crown Publishers Inc., 1974. pg. 464.

-

Ibid.

-

Robbins, Encyclopedia of Witchcraft, 461.

-

Francesco Maria Guazzo, Compendium Maleficarum, edited by Rev. Montague Summers, trans. E.A. Ashwin. Suffolk: Richard Clay & Sons: 1929. pg. 30.

-

Robbins, Encyclopedia of Witchcraft, 464.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Pico/Alberti, Strix, sig E3r, 124.

-

Pico/Alberti, Strix, sigs. E3r-v, 15-26.

-

Nicholas Jacquier, Flagellum haereticorum fascinariorum (Scourge of Heretical Enchanters), 1458, pg. 136.

-

Robbins, Encyclopedia of Witchcraft, 465.

-

Stephens, Demon Lovers, pg. 21-22

-

Girolamo Visconti, Opusculum de striis, videlicet an strie sint velud heretice iudicande (A Little Work about Witches), 1490, fols. 2r, 6v, 4r.

-

Robbins, Encyclopedia of Witchcraft, 466.

-

Ibid.

-

Stephens, Demon Lovers, pg. 101.

-

Guazzo, Compendium Maleficarum, 31.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Robbins, Encyclopedia of Witchcraft, 466.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Robbins, Encyclopedia of Witchcraft, 463.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Edward Bever (2009). “Witchcraft Prosecutions and the Decline of Magic”. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 40(2), 263–4. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40263656.

-

Ibid.

-

Beaver, “Witchcraft Prosecutions and the Decline of Magic”. Pg. 264.

-

Donald, Palumbo (1986). Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film. Greenwood Press. pp. 40–42.

-

Chu, Petra Ten-Doesschate (2006). Nineteenth Century European Art, 2nd Edition. Prentice Hall Art. p. 81. ISBN 0-13-196269-8.

-

Dr. Noelle Paulson, “Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed March 26, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/henry-fuseli-the-nightmare/.