Part 1

Content Warning: this essay contains descriptions and discussions of assault and rape.

[Theologians’] fantasy of witches’ corporeal ravishment translated their own desire for an overwhelming intellectual conviction, one that would annihilate their involuntary resistance to the idea of demonic reality

Walter Stephens, Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief, 26

Though the study thus far has focused primarily on erotic monsters in media and popular culture from the 20th and 21st century, the influence of erotic monsters predates this time frame by centuries. As such, this week we’re going to look at the surreal and near-obsessive fixation Europeans had towards erotic monsters during the Middle Ages relying upon Dr. Walter Stephens’ theory of the “Crisis of Belief”, and the role erotic monsters played in witch accusations, sexuality, and the churches’ desperate need for religious rehabilitation.

Overview

During the Middle Ages, a persistent wave of hysteria washed over Europe. Across the continent, men, women, and children were accused of practicing or participating in witchcraft, these accusations based on both a complicated and variable number of motivations, not all of which were spurred by what many believe to be driven wholly by misogyny.

Christinia Larner asserted that though witch-hunting criminalized women as a group, “witchcraft was not sex-specific but it was sex-related” due to the “substantial proportion of male witches in most parts of Europe means that a witch was not defined exclusively in female terms”.1 Despite the erroneous assertion of radical feminists like Andrea Dworkin that approximated 9 million or more female victims died from witch-hunting, a more realistic figure is that approximately 30-60,000 victims of both genders died within 300 years.2

This is not to undermine the role of violent misogyny in witch-hunting. In the case of Scotland—who zealously took to witch-hunting more so than neighboring countries like England because Scotland appropriated the witch-hunting patterns established on the Continent3—of an approximate total number of 3,837 accused, 84% were women, 15% were men, and 1% were unknown sex.4 Witchcraft theorist books like the infamous Malleus maleficarum, written by Heinrich Kramer, outlined explicitly how women were naturally predisposed to evil and drew evilness to themselves through their insatiable lust. One such passage from the Malleus states: “Women do all things because of carnal lust, which…is insatiable in them. Wherefore for the sake of fulfilling their lists they consort even with devils” and that witches “indulge in diabolical filthiness through carnal copulation with incubus and succubus demons…devoting themselves body and soul [to devils].”5

The misogynist ideology concerning the corrupting lust of women was not conceived during the Middle Ages, but rather, can be traced back to Adam and Eve in which Paul states that “the serpent seduced Eve by his craftiness”.6 Eve’s corruptible desires laid the groundwork for misogynistic ideology decades afterwards, especially by church clergy like the theologian and bishop of Milan, Ambrose, who concluded that “if Eve’s door had been closed, Adam would not have been deceived and she, under question, would not have responded to the serpent. Death entered through the window, i.e. through the door of Eve.”7 Much like Heinrich Kramer, theologian and partial archbishop Isidore of Seville believed that the libidinous appetite of women was intrinsic to them, and that they were even named for it based on “the word femina” which derived from Greek to describe “the force of fire because her concupiscence is very passionate: women are more libidinous than men.”8

Yet, it was women’s supposed “libidinous” appetite that allowed the literate elite, specifically the church clergy, not only a closer proximity to corporeal beings, but provided the proof they were so desperate to reinforce across Europe. To iterate Dr. Walter Stephens’ hypothesis, misogyny was the catalyst rather than the ultimate goal of the church. Literate elite wielded misogyny so that they could exploit patriarchal oppression to “reinforce demonology—and, ultimately, a theology” to resist skepticism that demons, and other corporeal figures and spirituality at large, were not real.9 Misogyny, especially the “insatiable lust” of witches, was ideologically useful—necessary—in proving the physical existence of spiritual bodily contact through sensory data and bodily experience, as witches were the only ones who could identify demons and devils. Stephens contextualizes clergy and witch theorists as metaphysical voyeurs who necessitated the insatiable sexual desire of witches for legal proof of the existence of demons. Even Kramer admits that the function of the witch is to “make credible the notion that devils have regular bodily interactions with human beings”.10

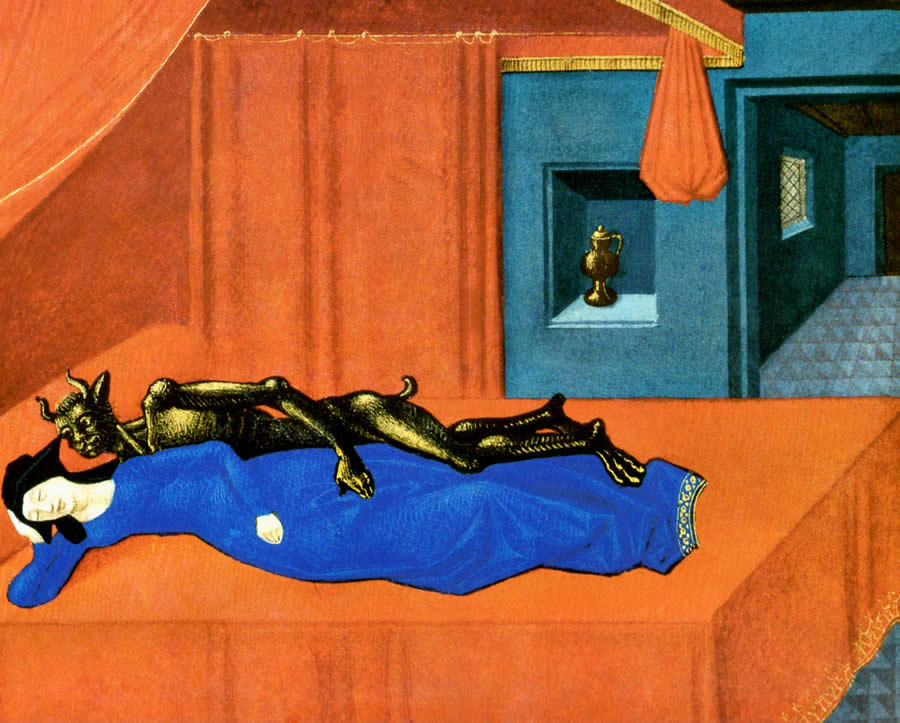

Per Stephens: “Without a diabolophany, a shattering personal encounter with a demon, the need for belief in demonic reality could never be satisfied”.11 These religious anxieties were then violently forced upon the people of the Middle Ages in a need for constant reaffirmation, extracted through torture and force as “proof”, and reinforced as “truth” through witch theory treaties and literature. In fact, demonic copulation did not come about during witchcraft trials until the torture stage, many of which were scripted, to produce satisfactory answers for the interrogators that reaffirmed proof of corporeal relations.12 For the church, sex was a mode in which they would obtain not only irrefutable proof of demons, but knowledge of them as well. The more descriptive a witches’ “confession” about the physical body of their demon lover, or, carnal knowledge, the more tangible proof clergy had at the indefinite existence of demons and corporeal beings.

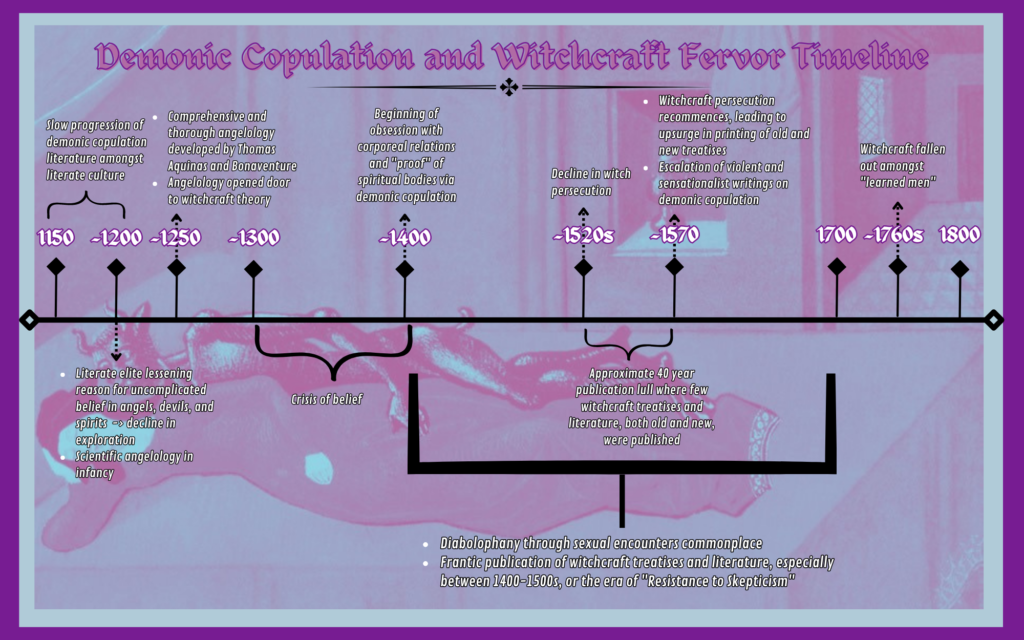

Timeline

Visualizing a timeline helps to clarify and follow the shifting attitudes and witchcraft theologies that occurred between 1150 and the late 1700s. Though not widely believed, nor fervently enforced, demonology and angelology began to take form in 1150. Because the literate elite did not have reason for uncomplicated belief in angels, demons, and spirits, there was not a need for “scientific” exploration (as loose as the term scientific can be).13 However, this did not mean that demons did not exist within the culture at hand. Most famously, perhaps, for its indirect but crucial feature was the incubus in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain (1136) that sires Merlin, the ‘most ubiquitous wizard figure in Western culture’.14 In a speech to British King Vortigern, Merlin’s nun mother states:

[Upon your soul and mine, my lord king, I knew no man who begot this child

of me. One thing, however, I do know, that when my companions and I were

in our cells, someone resembling a handsome young man used to appear to

me very often, holding me tight in his arms and kissing me. After remaining

with me for a while, he would suddenly disappear from my sight. Often he

would talk to me without appearing while I sat alone. He visited me in this

way for a long time and often made love to me in the form of a man, leaving

me with a child in my womb. In your wisdom, you should know, my lord, that

in no other way have I known a man who could have been this youth’s father.]15

It appears as though Merlin’s mother had been visited in the night by a corporeal being. The creature’s description mirrors demon attributes that would become commonplace centuries later in witchcraft treatise such as: the handsome and human disguise, approaching the nun during sleep, and the sudden disappearance after sex.

It is unclear just what exactly the creature was—be it an incubus, demon, or devil, that is unclear—but the creature’s definitive otherworldliness allowed for Merlin to possess powers of wizardry.

Still, demonology was in its infancy, and would not see progress until approximately 1250 when religious theologians like Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure produced comprehensive and thorough angelologies, thus opening the door to witchcraft and demonology theory.16 Things escalated quickly after 150 years of slow progress: by approximately 1300, the crisis of belief in the reality of corporeal beings had metastasized within the church, escalating over a century until the obsession with obtaining physical proof of corporeal beings evolved into an outright fixation that manifested itself not only in violent witch trials, but the boom of witchcraft treatises and literature that listed the various ways in which people, witches specifically, had had physical interactions with demons, thus demonstrating their existence. The late 13th century created a “search for precision and certainty about a world that was invisible to humans” and “generated significant perplexities and doubts”.17 As such, the 1400s marked the beginning of the obsession for demonology and witchcraft theory especially through demonolatry, or sexual relations with demons. Early on within the demonology craze of the 15th and 16th centuries, interactions between humans and demons was markedly different than what it would later develop into, specifically how women received pleasure during demon copulation. This was reflective within literature and treaties, such as Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola’s Strix, sive de ludificatione daemonum or The Witch; or, On the Illusions of Demons. The book, originally published in Latin in 1523 and later translated into vernacular Italian in 1555, was a reportorial witchcraft treatise adapted into a dramatic reprisal dialogue between four characters, three male (skeptical) interrogators and one female witch.18 Strix, though technically fictional, was based on a witchcraft trial Gianfrancesco had participated in and stood as a theatrical documentary investigation. The book evaluated at length the veracity of Strix (the witch) and her claims of demon copulation, specifically focusing on the witch’s assertion that the sexual act was mind-blowingly pleasurable. Below, one such interrogator from the book, Dicastes, puzzles through the idea that demonic copulation was intensely satisfying for Strix:

Dicastes: Witches claim they are so overcome by [sexual pleasure] that they swear there is no pleasure like it on earth. And I can think of several reasons why that would be true. First, because those rebellious spirits put on the most pleasing face. Next, because their [virile] members are of uncommon size. With their faces they delight the eyes, and with their members they fill up the most secret parts of the witches. And beyond that, they pretend to be in love with them, which is perhaps the most welcome of their miserable miracles. And probably they can stimulate something very deep inside the witches, by means of which these women have greeted pleasure more than with men.19

This intense pleasure was not relegated only to the female Strix, either. Dicastes continues to describe how succubi produced a similar kind of otherworldly pleasure for men as well, which historically aligns with the large number of male witches who were accused of demonolatry within countries like Italy, such as the 7 men out of an accused 10 witches that Gianfrancesco not only played a hand in their torture and subsequent murders, but based his book upon.20

In 1470, for example, Dominican Giordano (Jordanes) da Bergamo wrote his own treatise in which he describes the biographical (as much as it perhaps ever could be) story of a hermit who had lived in northern Italy. The Devil had taken the appearance of a beautiful woman and seduced the hermit until both had passionately embraced. After the deed had been done, the Devil cast aside his disguise and gleefully taunted: “Look what you’ve done! I’m not a girl or a woman, in fact, but the Devil!” Having obtained what he needed (semen) for further production of demons and devils, “the Devil disappeared immediately, proving that his words were true” and that he was, in fact, the Devil. However, the hermit had been so drained of his semen that he shriveled up and died a month later.21 I suppose this is why the French call an orgasm, “le petit mort”, a little death.

Though diabolophany through sexual encounters was a commonplace occurrence and accusation between the 1400s through the 1700s, a lapse in witchcraft theology and trials occurred approximately in the 1520s. A 40-year lull drastically slowed the production and publication of both new and old witchcraft treaties and literature, however, this lull was not long-lived and by the 1570s, would recommence once again, this time more fervently and violently, escalating in yet another publication proliferation of witchcraft treaties and literature, both old and new.

After 1570, the accused during confessions no longer spoke about the intense pleasure they received during demonic copulation, but rather attested to how painful, unwanted, and unpleasant it was. Confessions were “far more violent and lurid than those typically of the period ending in the 1520s”, casting aside descriptors of intense pleasure or physical exhaustion for more sensationalist descriptions.22 Pleasure and exhaustion were no longer adequate signs of demonic copulation and as such, the devil had to “demonstrate his virility by going beyond the bounds of virisimilitude (and of verisimilitude)”.23 This meant that demons’ and devils’ penises grew (heh) to exaggerated and over the top lengths, “[their] ejaculate was incredibly copious; both [penis and semen] had to be so cold as to cause intense pain”, and the number of members doubled, sometimes tripled, for simultaneous penetration.24 This frantic reestablishment of resistance to skepticism would last until the late 1700s, until which time witchcraft theory would begin to fall out of favor amongst “learned men” and become nothing more than “mere old wives’ fables”.25

Conclusion

Having briefly outlined and contextualized the reason for demon copulation during the Middle Ages, Part 2 will focus on the specifics of demon copulation and the details within the accused’s confessions. This will include the physical appearance of demons and devils, how sex took place, and how sex was described.

Works Cited

- Larner, Christinia. Enemies of God. Maryland: John Hopkins University Press, 1981. pg. 92.

- Walter, Stephens. Demon Lovers: Sex, Witchcraft, and the Crisis of Belief. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2002. pg. 4.

- Stephens. Demon Lovers. Pg. 102.

- “The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft: Introduction to Scottish Witchcraft”. The University of Edinburgh. http://www.shca.ed.ac.uk/Research/witches//introduction.html.

- Kramer, Heinrich. Malleus maleficarum, fol. 54V (p. 111), emphasis added.

- Paul, 2 Corinthians 11:3.

- Ambrose, On Virginity, trans. Daniel Callam, Peregrina Translation Series 7. Toronto: Peregrinqa, 1989). pg. 13, 81.

- Isidore, Etomologias, xi.24.43.

- Stephens, Demon Lovers, 37.

- Ibid, 36.

- Ibid, 87.

- Ibid, 15.

- Ibid, 26.

- Riga, Frank P. ‘Merlin, Prospero, Saruman and Gandalf,’ in Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language, ed. Janet Brennan Croft (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), pp. 196, 198 [196-214].

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, ed. Michael D. Reeve, trans. Neil Wright (Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press, 2007), Book VI, 11. 531-40.

- Stephens, Demon Lovers, 26.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 89.

- Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola, Strix, sive de ludificatione daemonum, sigs. E3r-v; Pico/Alberti, 15-26.

- Stephens, Demon Lovers, pg. 89-90.

- Giordano da Bergamo (Hansen, ed), pg. 198.

- Stephens, Demon Lover, pg. 101.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Wesley, John. The Journal of the Rev. John Welsey, Enlarged from Original Mss., with Notes from Unpublished Diaries, Annotations, Maps, and Illustrations. Ed. by Nehemiah Curnock. 8 vols. London: R. Culley, 1909-16. 5:265.