While Dracula was a figure whose mysterious and dangerous sexuality was primarily aimed at heterosexual women as a marketing tactic for all of the Count’s film history, the queer subtext of both the book and the movies remains persistent and, thanks to adaptations, more and more explicit. (Who could have foreseen this? The guy with a flair for dramatics and capes is queer? Not me!)

Truthfully, I always found it a little silly when talking about strictly heterosexual vampires (is there such a thing?); like, what do you mean you are cursed to live forever and you’re not gonna spend your eternal night getting weird with it and exploring different avenues of pleasure? What else are you going to do? What do you mean you hypnotize your victims to feast upon them, men or women? Sounds fruity to me. ANYWAY…

Today, our media is packed with great queer vampires: from the brilliant new AMC adaptation Interview with the Vampire to the goofy but lovable vampire crew from What We Do in the Shadows, our beloved gay vampires contextually come from a long line of queer coded vampires. So, where did they come from? And why does it always go back to Dracula?

Stoker: Driven Wilde with Sinful, ‘Decadent’, Lust

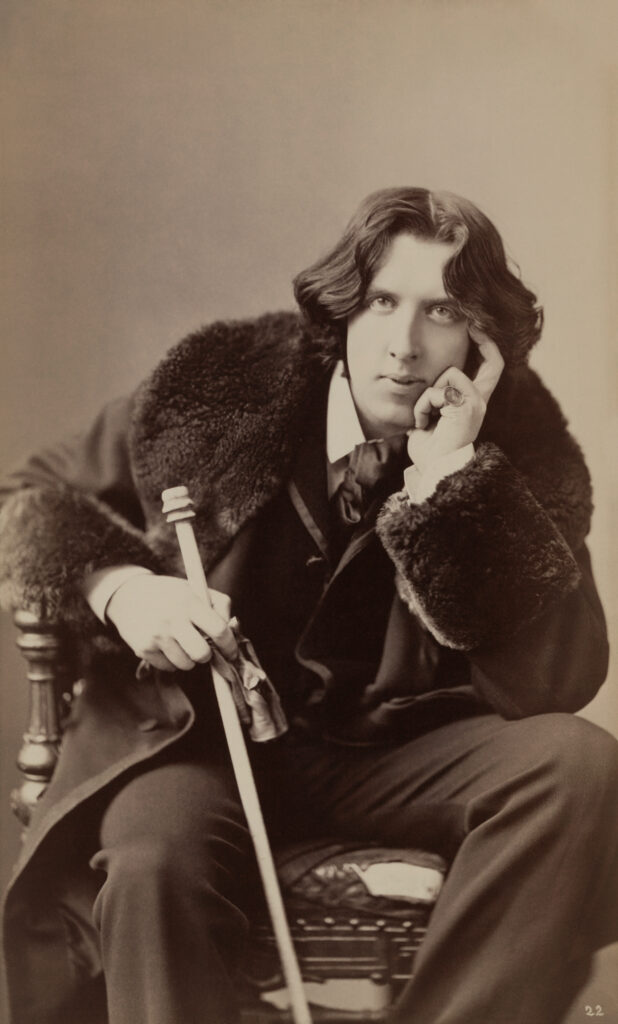

Despite establishing himself during the 1870s as “an open member of that nascent homosexual culture centered around Whitman”,10 Stoker was more persistent about maintaining the status quo, especially relating to gender, and “believed in manliness, chivalry, and bluff good humor”.11 This was a stark contrast to Wilde who was only just beginning to question societal norms and found them “utterly irrelevant”.12 Wilde was uninterested in participating in the Philosophical Society despite joining and scoffed at Trinity’s meat-head athletic culture where boys “thought of nothing but cricket and football, running and jumping”.13

Unable to avoid one another in their very tight circles, Wilde was trapped in Stoker’s growing shadow. He constantly competed with Stoker for the affections of multiple people in his life: his parents, who viewed Stoker like the perfect golden-child, older brother; Wilde’s own girlfriend, Florence Balcombe, who left Wilde and hastily married Stoker in 1878 after keeping their engagement secret from everyone; and Sir Henry Irving, an English stage actor who was an idol of Wilde’s, that Stoker would later work with as Irving’s business manager.14

Could you imagine inviting this scoundrel around to family Christmas parties, forced to listen to your parents go on and on about how wonderful he is, only for him to steal and marry your girlfriend right out from under your nose? It would be grounds for murder for me personally, but for Wilde “Florence’s presence transformed a competition into an erotic triangle”.15 And for Stoker? These triangulated rivalries, especially his complex relationships with Wilde & Irving and Wilde & Florence, were ways in which Stoker could “disseminate his homoerotic desires into several non physical circuits”.16

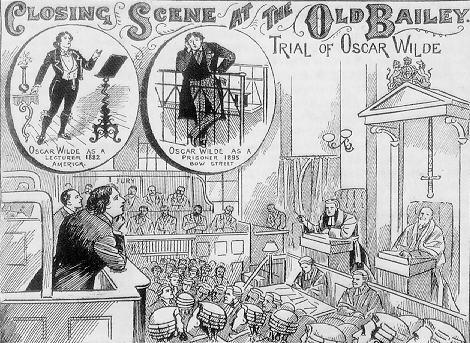

And then everything changed in 1895. On May 24th, Wilde was convicted of sodomy, and suddenly Stoker, who was still processing his sexuality with guarded secrecy, pivoted fearfully into urgent and reactionary repression. Wilde would not be found guilty by English courts until 1912, however in that time Stoker pulled a full 180 about his beliefs not just concerning literature, but abandoned his public love for Whitman as well.

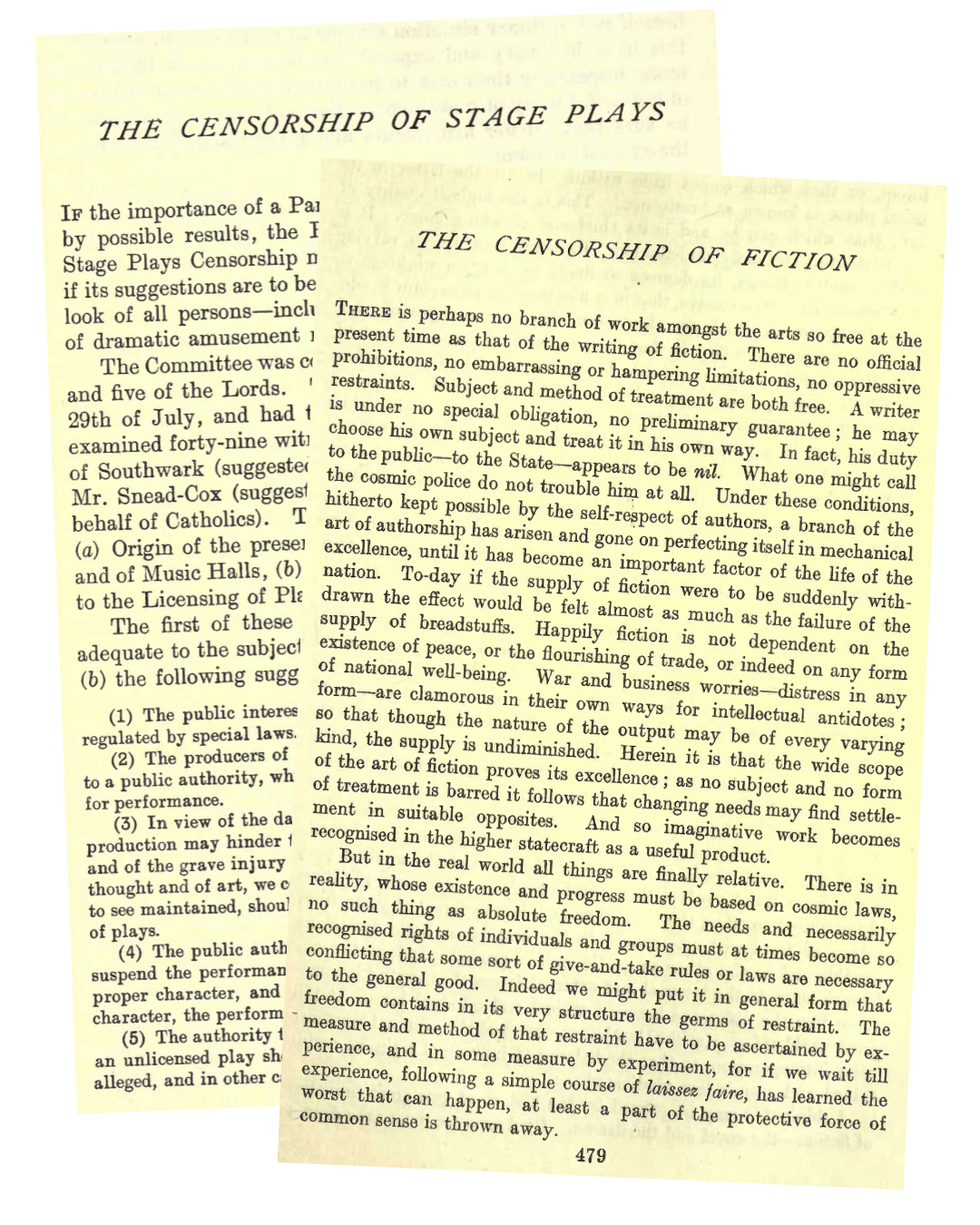

He wrote two essays titled “The Censorship of Fiction” (1908) and “The Censorship of Stage Plays” (1909) in which he vociferously called for the state censorship of sexually-exciting narratives and police repression of ‘[his] kind’. He targeted homosexuality using coded terms like “decadence” (remember this term, it will be used for decades afterwards in reference to queerness), “indecency” and “morbid psychology” to (not-so) covertly attack the literature of writers like his once-beloved Whitman.17

Stoker argued that literature with homosexual themes not only brainwashed ‘normal’ readers to suddenly have queer desires (sounds very familiar to arguments we still hear today, doesn’t it?) but made readers suddenly lack control over those sinful vices, even likening the literature to addictive “noxious drugs”.18 In what can only be understood as immense projection, Stoker admitted that no one can control “the workings of imagination”, and so the only way to stop that process of thought, to “prevent [decadence], the censorship must be continuous and rigid. There must be no beginning of evil, no flaws in the mason-work of the dam”.19

Stoker was purposeful in his use of the term “decadence” when referring (not so implicitly) to queerness. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the term “decadence” was largely associated with homosexuality because of “The Decadents”, a macabre and queer movement of poets and artists that focused on symbolic themes like abnormal love, necrophilia, eroticism, and women’s corpses in their work.20 Disgusted by “corruption and rampant materialism of the modern world”, they found escapism in aesthetic, fantastic, erotic or religious realms.21 These tortured artists were pale and slightly effeminate people who claimed they possessed a woman’s soul trapped inside themselves, a gendered inversion that played on the era’s understanding of homosexuality as as a third gender.22 This small but avant-garde movement was occupied by artists and writers like Théophile Gautier, Charles Baudelaire, Félicien Rops, and of course, none other than our persecuted Oscar Wilde.23

In fact, Wilde’s book The Picture of Dorian Grey (1891) thematically embodied the Decadent movement by featuring “imagery of the monster queer:…a sexually active and attractive young man who possesses some terrible secret which must perforce be locked away in a hidden closet”.24

In response to the avante-garde movements that were taking place during the end of the century came the rise of pseudo-scientific and fascist theories that monstrasized and criminalized movements like the Decadents. Max Nordau’s 1892 Entartung (Degeneration in English) postulated that the “‘abnormal’, embodied by the Decadents themselves, were ‘monstrous freaks of nature who belied humanity’s claim to evolutionary perfection'”.25 And so, for better or worse (mostly worse), the term “Decadence” evolved into a euphemism for homosexuality by the end of the 19th century.

Okay, so what the hell does any of this have to do with Dracula?

Though Stoker had been planning to write Dracula for quite some time, it was only one month after Wilde’s conviction that he began to actually write the now classic novel.26 One month. Imagine you are Stoker, a man caught between wanting to abide by the status quo of masculinity and sexuality, unable to control your own lustful thoughts as they veer into dangerous, queer territories, when your friend and rival for over 20 years is arrested for sodomy? That the very things you yearned for were now a public spectacle on trial by a violently homophobic system, personified by none other than your competitor and friend?

The narrative of Dracula suddenly can be reinterpreted in this vastly different context, the character and plot injected with Stoker’s terror, disgust, repression, and queer anxieties. The conflict and fear between Jonathan Harker and Count Dracula mirrors that of the conflict between Stoker, his repressed urges, and Wilde, with Dracula representing “the ghoulishly inflated vision of Wilde produced by Wilde’s prosecutors; the corrupting, evil, secretive, manipulative, magnetic devourer of innocent boys…the complex of fears, desires, secrecies, repressions, and punishments that Wilde’s name evoked in 1895”.27 As Schaffer explains, Dracula is not so much an embodiment of Wilde, but “Wilde-as-threat, a complex cultural construction not to be confused with the historical individual Oscar Wilde”.28

Oscar Wilde, the self-proclaimed Decadent obsessed with Victorian Gothic occult and eccentric, flamboyant fashion of velvet suits and huge fur coats, who stood in stark relief to Stoker, a man that had tried desperately to conform to and uphold societal norms. Oscar Wilde, the man Stoker had once rivaled with for the affections of two different people, now destitute, all his belongings gone, and his head shaved as he spent two years in jail for his “crimes”.29

Wilde’s identity as a Decadent and a queer man automatically categorized him as a gendered Other, as something neither male nor female, but “inhabiting a no-man’s land like the Undead who were neither dead nor alive”.30 Through the prosecution of the court, Wilde’s image metastasized into a threat that could not only prey upon men, but infect and transform his victims into something “monstrous” as well, just like Dracula. It didn’t help that culturally, homosexuality and anal sex was associated with defecation, dirt, and decay either.31 This was in part due to fascist ideology linking degeneration with homosexuality and movements like the Decadents, but it was also further reinforced culturally by the emergence of queer people as vampires in literature, like Carmilla (1871). Stoker himself was influenced by Sheridan le Fanu’s gothic lesbian tale, Carmilla, while the German gay magazine Der Eigene (1896-1931) “contained much vampire imagery in its fiction and at least one complete vampire story”.32 As Schaffer poignantly states, “To homophobes, vampirism could function as a way of naming the homosexual as monstrous, dirty, threatening. To homosexuals, vampirism could be an elegy for the enforced interment of their desires”.33

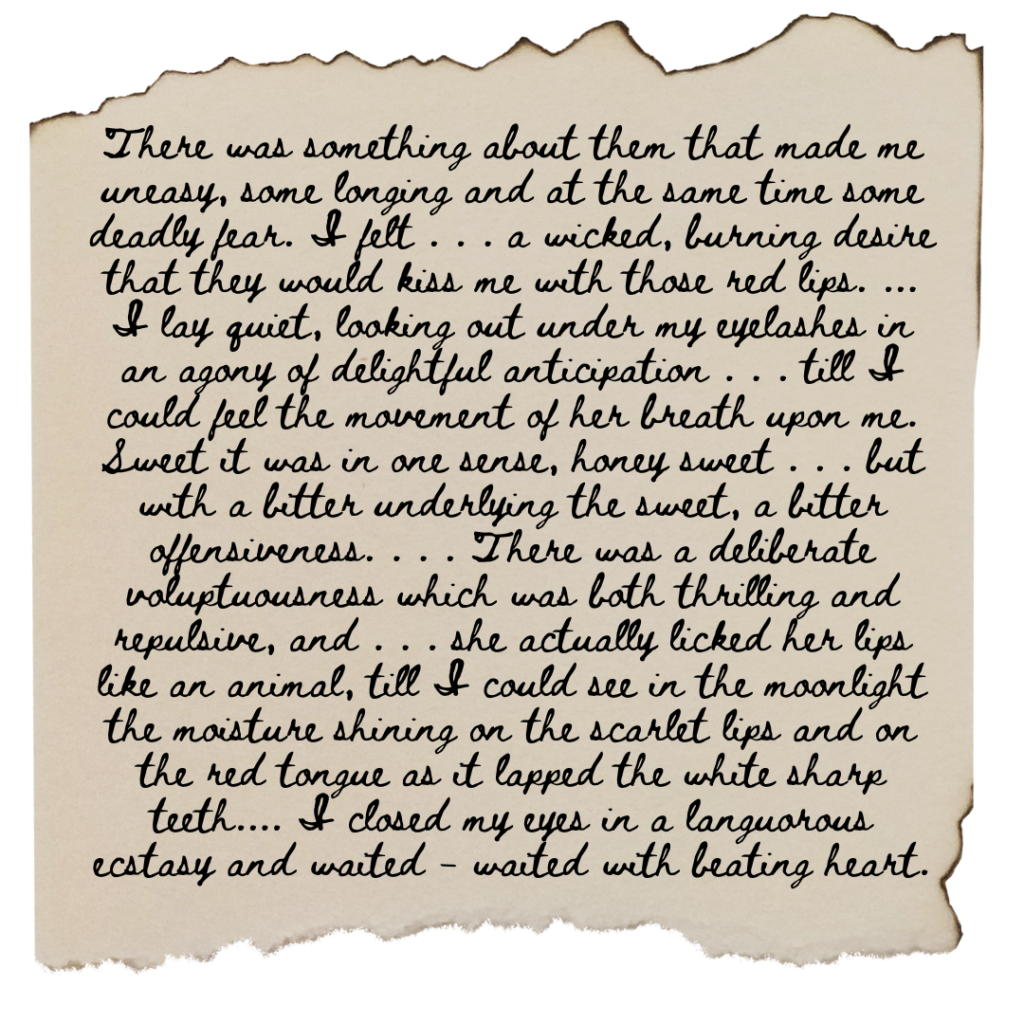

For a man who demanded that the state repress sexual narratives and homosexuals, his work even by today’s standards is both erotically and homoerotically charged. Dalton Valette recorded the frequency of sexual imagery, noting that “‘kiss’ or ‘kisses’ was used 42 times, ‘lips’ 62 with ‘voluptuous’, often referring to the vampire’s ruby red lips, coming up 12 times”.34 Meanwhile, James V. Hart, the screenwriter and co-producer for Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) described the novel as an “extraordinary erotic, oral, wet, feverish novel that people avoided like the plague”.35 Take, for example, the scene in which Harker is approached by a trio of vampires while trapped in Dracula’s castle:

In response, one of the vampires tells Harker, “There are kisses for us all”. Apparently Dracula doesn’t like the idea of Harker sharing kisses with other vampires at all because he then appears to possessively proclaim, “This man belongs to me!” Which is a…curious reaction, to put it mildly.

These projections are made doubly more complex when you throw Florence/Mina into the mix: the homosexually-charged, competitive triangle that occurred between Stoker, Wilde, and Florence is duplicated between Harker, Dracula, and Mina. I mean, come on, just look at this scene and tell me it’s not homoerotically charged:

Leonard Wolf summarizes this scene in “The Essential Dracula” as being “crammed with implications, nearly all of them sexual” what with it featuring “a vengeful cuckoldry…a ménage à trois . . . mutual oral sexuality . . . [and] the impregnation of Mina”.36 Never mind the fact that Harker’s description of being flushed and “breathing heavily as though in a stupor” sounds very similar to that of an orgasm. All of this takes place within the context of Harker as, once again, a passive participant in a tableau of desire, the roles of domination and submission fulfilled. Except this time, instead of the thrill of being pounced upon by vampiresses, he’s forced to watch his wife be claimed by Dracula. Turns out Stephanie Meyer isn’t the only vampire author obsessed with cuckoldry.

The triangulated relationship between Dracula/Jonathan/Mina has been described by many academics as portraying the male homosocial triangle that allows men to engage with one another through a safe buffer: a woman. Eve Sedgwick describes in her book, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire, that the inclusion of women in these homosocial/sexual charged relationships deflects the threat of homosexuality by creating a safe triangular configuration rather than a more direct male-to-male partnership.37 In this way, while this configuration primarily “serves to bolster patriarchy”, men are able to express their “sublimated or repressed homosexual desires” through the conduit of a woman.38

Schaffer’s entire argument is that Dracula represents the subliminal and complex queer desires of its very repressed author, however, while that is true, I would broaden the argument to include subversive, transgressive, desire in general. Stoker focuses obsessively on desire and lust not just in Dracula, but in many of his other works as well, especially the sexuality of women. Sexual forwardness, for example, is a common characteristic for his villains. In his book The Lair of the White Worm, the sexually-voracious character Lady Arabella is portrayed as a horrible primeval monster. In The Man, Stephan Norman is punished for her adolescent forwardness and is forced to learn how to be more feminine. And of course, the three vampire women that Harker first encounters in Dracula radiate sexuality and look to devour him (in both senses of the word). They are, in the end, destroyed for not abiding by their proper gender roles.39

Stoker’s concerns about rampant sexuality running amok and unraveling the fabric of decent society stemmed from the emergence of the New Woman, which was a feminist movement that advocated for greater freedom, physical activity, and most worriedly, sexual agency to initiate relationships, alternatives to marriage & motherhood, and open discussions about contraception & venereal disease.40 The New Woman found herself to be culturally maligned with groups like The Decadents as she was “perceived to have ranged herself perversely with the forces of cultural anarchism and decay precisely because she wanted to reinterpret the sexual relationship. Like the decadent, the heroine of New Woman fiction expressed her quarrel with Victorian culture chiefly through sexual means–by heightening sexual consciousness, candor, and expressiveness”.41 As Wilde’s inflated public caricature was represented by Dracula, Stoker created his own distorted portrayal of the New Woman through the female vampires and villainesses: sexually voracious, aggressive, and completely lacking in maternal feelings. In fact, it is because of their inversion of gender that Stoker revokes their womanhood entirely: “I am alone in the castle with those awful women. Faugh! Mina is a woman, and there is nought in common. They are devils of the Pit”.42 This analysis aligns with Elizabeth Signorotti’s theory that Dracula sought to “repossess the female body for the purposes of male pleasure and exchange, and to correct the reckless unleashing of female desire in Le Fanu’s Carmilla”.43

Dracula, then, is a complex text that seeks to demonize that which Stoker has deemed corrosive to society at large, and himself, but the book instead “functions as both accusation and elegy”.44 It lays bear his vices, his repulsion, his yearning, his fear, and ultimately his desperation to reinforce heterosexist cultural norms by making a monster of subversive desire. Whether it was the New Woman or the queer Decadent man, the specter of sexuality and the way it subverted gender haunted Stoker. Just as Stoker spoke about homosexual-themed literature and how it needed to be repressed, he can’t help but demonstrate (and all but admit to) his open desires in Dracula as though to showcase their danger, only to reaffirm that such danger can only be dealt with by destroying it. Rather, the coffin was now “as shameful a palace of simultaneous retreat and safety as the closet” for both Dracula and Stoker.45

He'll Suck You Dry!

Oh my god, all that yapping and we’ve only just made it into the early 1900s. Unfortunately, not much had changed since the late 1800s, especially relating to public opinion on homosexuality. There was a brief moment during the 1920s in which queerness was fashionable in certain social spheres, and you saw phrases like “lesbian chic”, “pansy craze”, and experimental bisexuality emerge, however, after the stock market crash in 1929, that “decadent” sort of queerness disappeared as scarcity set in.46 By the 1930s, homosexuality was once again being repressed by various social reformers and psychologists alike.

At best, queerness was ambivalently thought of as “a gender deviance than sexual-object choice”; at worst, it was a criminal offense associated with “sadism, masochism, incestuous desires, jealousy, paranoia, criminality, and repression to baser animalistic instincts” by psychologists and psychoanalysts like William Stekel.47 Deviance from heterosexist gender dynamics (e.g. women as soft and docile & men as confident and aggressive) was thought not only pathological by many psychologists, but theorized to be responsible for the creation of queer children if the nuclear family demonstrated any sort of deviance from their “inherent”, “natural”, gender norms.48 Arguments took place within the medical community over whether homosexuality came forth from nature or nurture, i.e. does the nefarious homosexual exist outside the “natural Order”, or, was homosexuality something that existed potentially in everyone, dormant?

All of this is to say: psychologists didn’t know dick-all about where homosexuality arose from, and it scared them; hateful, it emboldened society to reinforce heteropatriarchal structures even more as a safety precaution against the “creation” of more queers.

You can see then how this mode of thinking was not only conducive to Othering queer people and monstrosizing them, but code their Otherness within horror cinema. Because what could be more chilling to heterosexual society than the thought of queerness as either an abnormal force that existed in threat to your very comfortable livelihood or that queerness lived dormant within you, waiting? Forget the abject poverty that had plunged the United States into despair and struggle, society had bigger fish to fry: worrying about homosexuality.

Hollywood cinema would largely be influenced by the German Expressionist movement which wedded “its queer characters and occurrences to a visual style drawn from modernist paints”.49 The Expressionist movement produced groundbreaking horror films like the Dracula knock-off Nosferatu (1922), which was made by the gay director F.W. Murnau.50 At this time, Expressionism and modern art was associated with queerness not just because many of its practitioners were homosexuals, but because the movement positioned itself antithetical to “normality”. In response, Nazis within Germany emphasized the link between homosexuality and abnormality, denouncing modern art as having been “polluted by primitivism” (Jewish people, homosexuals, communists, and other social deviants), and categorized it derisively as “Degenerate Art”.51

For both Nazi Germany and 1930s Hollywood cinema, the homosexual was a threatening monster signified by their “decadence and depravity”.52 Although, who amongst us is surprised that both Nazi Germany and the United States shared similar ideology: it’s pretty much that Spider-Man meme where identical Spider-Man’s point at one another.

Like the German Expressionist movement, 1930s classic Hollywood horror cinema possessed a large number of queer people who worked as producers and actors. James Whale, allegedly dubbed the tongue-in-cheek nickname the “Queen of Hollywood” by industry wags, directed four of the classic period horror films for Universal: Frankenstein (1931), The Old Dark House (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), and the Bride of Frankenstein (1935).53 Whale’s films, as well as other classic Universal horror films, “exploited not only homosexual signifiers in conjunction with their gothic villain’s crimes, but often a whole range of queer sexual behaviors”.54

Harry M. Benshoff outlines in his book Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film key subtextual signifiers that coded a monster or villain as queer such as:

- Possessing a mysterious origin

- Being finely acculturated, dandified, with bizarre modes of dress, make-up, and deportment

- Having a love of the arts

- Being foreign, especially possessing European decadence/British air

- The sado-masochistic villain/henchman dynamic who creates life through science

- The villain/monster disrupting the harmony of a heterosexual couples relationship

- The villain/monster leading “double” lives.55

For our beloved Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi, Dracula’s queer-coding was founded in a number of these signifiers. For starters, Lugosi’s foreignness to WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants) audiences marked him as an ethnic Other, “a European mystery man, given to odd excesses, “decadence”, and the supernatural”.56 The boundaries between xenophobia, racism, and homophobia blurred as the monster’s stereotypical signifiers were conflated and blurred, contributing to the perception that foreign lands, including the oh-so exotic Europe (lol) was a place of sexual decadence. It sounds so surreal that the American public at the time was so racist that they both racialized and feminized other white people, but it was culturally accepted, and even written about in media like Harper’s Monthly Magazine in which articles mused about “…[European people developing] to a state where perversion is a rule…”.57 It was not so long ago (only 18 years prior!) that Oscar Wilde, the queer Decadent himself, was convicted of sodomy in London.

Universal ensured the Otherment of queer people through the exploitation of homosexual signifiers, as well as portraying the villains and monsters as sexual deviants too, mirroring their perversions with those listed by psychologists about homosexuality. Pedophilia, cannibalism, necrophilia, and oral sex (🎵one of these is not like the others🎵) were central, recurrent, or hinted themes within the vampire narrative, especially that of Dracula.58 The classic horror film was not concerned about drawing distinctions between homosexuality and sexual perversity; instead it used those pre-existing fears to sensationalize queerness and “to titillate, to thrill, to repulse”.59

With Lugosi’s elegant aristocratic fashion; pale face; dark painted lips; coiffed hair; and resounding foreignness, his portrayal of Dracula played to American fears at the time, especially in conjunction with the “vampire’s ability to spread his monstrous condition”.60 Lugosi’s Dracula presented the terrifying, queer subtext that anyone could potentially be turned; that his kind of monstrosity was not one that was neatly contained to the periphery of society, but rather something that could trigger monstrosity in anyone. Though Dracula is capable of killing people, more often than not (and perhaps even worse than not) he spreads his monstrosity by sharing his blood with his victims, turning them into eternal creatures of the night. As even Dracula states himself, “There are far worse things awaiting man than death”.61 His vampirism is an infectious kind of monstrosity–his allure, his queerness, his abnormality–that even the characters are aware of, even if they don’t understand what he is. After Mina has been bit, she mournfully tells her beau Jonathan Harker, “No John, you mustn’t kiss me ever again” as though her new infliction is something she could spread to him as well.62 This is further reiterated when Dracula confesses to Van Helsing that, “My blood now flows through her veins; she will live through the centuries to come, as I have lived”.63 She has, in essence, been tainted.

One could argue that Dracula living in the decrepit ruins of an abandoned castle makes him all the spookier and there’s nothing more to be said about the setting choice; however, the decay and death that Dracula surrounds himself with harkens back to the queer gothic villain. Though he lives divorced from society and the living, he is not bound to that space: he is able to infiltrate society and close inner circles, even with that intense-ass and incriminating stare. Because of his ability to move freely within other’s intimate spaces, Dracula is a disruptive queer force that comes between the “assertively “normal” heterosexualized” Mina and John, “who serve as the center of the naturalized and normative heterosexual equilibrium”.64 Once a happy unit, Dracula turns Mina away from John and changes her personality entirely to someone that John hardly recognizes.

There was a lot of pearl clutching going on during the 1930s about the supposed immorality of movies that led to the creation of the Production Code, aka the Hays Code, which censored “(among other things) the depiction or mention of homosexuality, or “sexual perversion” as it was classified”.65 However, the Hays Code wouldn’t be enforced until 1934 by the Production Code Administration Seal of Approval, so the production of Dracula (1931) got away portraying a number of salacious things like (gasp) a lesbian couple who accompany Renfield to Transylvania.66 Execs, however, did draw the line at certain portrayals: they refused to show Dracula biting any of his victims, especially men, as they thought it was too sexually charged and homoerotic. To fix this, as Dracula draws upon the limp and unconscious form of Renfield, the film fades to black to censor the scene before the audience can see Dracula bite him. This censorship tactic would especially be deployed after 1934 when the Hays Code began to be enforced to appease the PCA about not showing anything gory, sexual, or homoerotic.

However, these narrative ellipses “heighted the risque connotations of monstrous attack” through implication, conflating violence and romance while inviting “spectators to assume that what occurred offscreen was as significant as what happened onscreen and what offscreen events were not solely acts of violence…”.67 The scene, without showing anything explicit, is sensually charged. As Renfield drops to the ground unconscious, Dracula’s wives creep closer to his slumped form in their gossamer gowns and hungry expressions; but there, Dracula appears from the periphery. The music peaks dramatically as Dracula’s presence dominates the scene; his wives acquiesce to him and slink back from Renfield. Dracula drops to the ground and kneels over Renfield’s form, just on the precipice of striking, before the scene fades to black. Yet the audience is still “left to speculate upon the precise nature of the attack: is it sexual, violent, or both?”68 Is Dracula’s bite as erotically charged as his wives’ would have been? What part of it was so taboo that it could not have been shown: the gore or the eroticism? The ambiguity of the scene is further emphasized by the fact that it is immediately followed with Renfield as Dracula’s babbling and mad servant helping him to sail across the tumultuous seas. He is alive, but at the cost of his sanity and freedom. Instead, their relationship displays the sado-masochistic queer coupling of the villain and his henchmen. Renfield is conflicted between being subservient to his master, while also not wishing to abide by Dracula’s demand to turn Mina into a vampire.

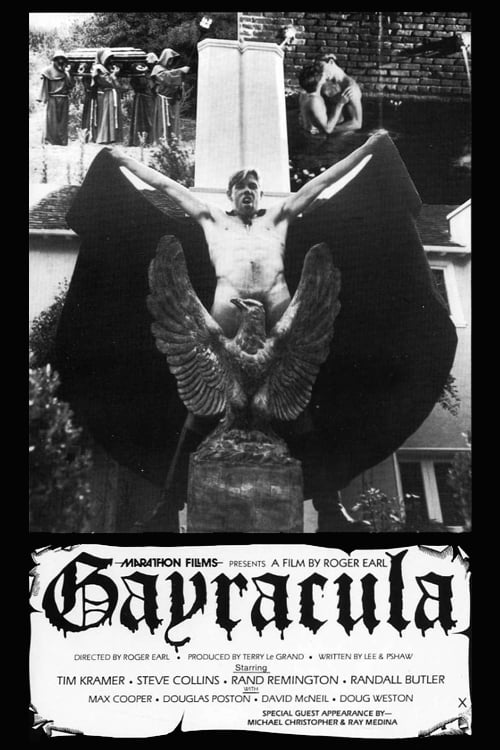

Dracula’s queer subtext would not stay relegated to Lugosi either. Rather, “the classical period produced several iconographic queer monsters whose homosexual undertones would become more and more prevalent as they were remade and adapted. These figures include the homosexual or bisexual vampire in Dracula’s Daughter and Mark of the Vampire”.69 After the 1930s, Dracula would continue to be an “embodiment of a certain cultural moment–of a time, a feeling, and a place”, especially in relation to queer sexuality.70 For example: during the 40s, Dracula represented the “Nazi-queer-monster” in Columbia’s Return of the Vampire (1943) (still played by Lugosi), directly associating the Transylvanian count with German threat; and during the late 60s and onward, the gay pornography scene centered Dracula in many smut films like Does Dracula Really Suck? (1969), Gayracula (1983), and Love Bites (1988).71 Dracula’s return to the screen time and time again was a reflection of “contemporary social movements or a specific, determining event…even if vampiric figures are found almost worldwide, from ancient Egypt to modern Hollywood, each reappearance and its analysis is still bound in a double act of construction and reconstitution”.72 Through all his iterations, Dracula has remained a cultural body, especially in relation to sexuality. As J.J. Cohen points out, it’s not coincidental “that Coppola was putting together a documentary on AIDs at the same time he was working on Dracula”.73

From the implicative, fade-to-black scenes in the 1931 Dracula to Coppola reinserting the titular book’s homoerotic dialogue (“How dare you touch him!” Gary Oldman’s Dracula yells at the vampire wives. “He belongs to me!”), the queer subtext of Dracula is a fluid and ever-changing thing throughout the decades. His coding is complex in nature–brought forth from repression, stereotypes, and the Othering of homosexuality–but nonetheless still resonates with many queer people as he is able to “slip imperceptibly from his distinctive nocturnal identity into the conformity and anonymity of a working-day persona–is his strongest armour and his greatest shame. It is his compromise with the world, a condition of his safe existence which nonetheless makes his encounter with the community of humans less than ideal in a liberal, modern world”.74

Works Cited

- McNally, Raymond T. Dracula was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987.

Schaffer, Talia. “‘A Wilde Desire Took Me’: The Homoerotic History of Dracula.” ELH, vol. 61, no. 2, 1994, pp. 381–425. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2873274. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 381.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 385

- Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 383.

- Ibid.

Benshoff, Harry M. Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997. Pg 18

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 390.

- Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, 392-393.

- Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, 384.

- Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, 393; Ellmann, Richard, Oscar Wilde (New York: Vintage Books, 1987), 34; Farson, Daniel, The Man Who Wrote Dracula (London: Michael Joseph Ltd., 1975), pg. 19.

- Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, 393.

- Harris, Frank. Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions, 2 vols. (New York: Printed and published by the author, 1916. pg. 41.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, 393.

- Ibid.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, 396.

Stoker, Bram. “The Censorship of Stage Plays”, 1908.

- Stoker, Bram. “The Censorship of Fiction”, 1908. Pg. 483, 485.

Stoker, Bram. “The Censorship of Fiction”, 1908. Pg. 481-482.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 19.

Tate Museum, “Decadence”, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/d/decadence.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 20.

Tate Museum, “Decadence”, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/d/decadence.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 20.

Walsh, Kerry. “Oscar Wilde and the Evolution of the Gothic in an Age of Epistemological Upheaval”, Cove, https://editions.covecollective.org/edition/oscar-wilde-and-evolution-gothic-age-epistemological-upheaval; Karschay, Stephan. Degeneration, Normativity and the Gothic at the Fin De Siècle. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. pg. 3.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 381.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 398

- Ibid.

Green, Cynthia. “Oscar Wilde: Of Dress Shirts and Dentures”, Feb 3, 2020 https://www.thevoiceoffashion.com/intersections/columns/oscar-wilde-of-dress-shirts-and-dentures-3541.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 398

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 398-9.

Dyer, Richard. “Children of the Night: Vampirism as Homosexuality, Homosexuality as Vampirism” Sweet Dreams: Sexuality, Gender, and Popular Fiction, Ed. Susan Radstone (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1988), pg. 48.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 399.

Valette, Dalton. “The queer horror of Dracula”, Salon, August 30th, 2022, https://www.salon.com/2022/08/30/dracula-queer-horror-bram-stoker/.

BLOODLINES: Dracula: The Man, The Myth, The Movies.

Wolf, Leonard. The Essential Dracula: The Definitive Annotated Edition of Bram Stoker’s Classic Novel. New York: Plume, 1993. pg. 337

- Eve Sedgwick, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 66.

Senf, Carol A. “‘Dracula’: Stoker’s Response to the New Woman.” Victorian Studies, vol. 26, no. 1, 1982, pp. 39. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3827492. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

Senf, “‘Dracula’: Stoker’s Response to the New Woman.” pg. 35.

- Dowling, Linda. “The Decadent and the New Woman in the 1890’s,” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, 33 (1979), pg. 440-441.

- Stoker, Bram. Dracula.

- Signorotti, Elizabeth. “Repossessing the Body: Transgressive Desire in Carmilla and Dracula”, Criticism, Vol. 38, No. 4, 1996. Pg. 607. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23118160.

Schaffer, “A Wilde Desire Took Me”, pg. 399.

Hughs, William.“’The taste of blood meant the end of aloneness’: Vampires and Gay Men in Poppy Z. Brite’s Lost Souls“, in Queering the Gothic. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009. pg. 143.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 33.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 31, 32.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 21.

Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 66.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 36, 40.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 36.

- Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 46.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 61.

Robert Dean Frisbie, “The Sex taboo at Puka-Puka,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine 162 (December 1930) 100.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 56.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 69.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 39.

Dracula, Dir. Tod Browning, Perf. Bela Lugosi, David Manners, Helen Chandler, and Dwight Frye. Universal Pictures, 1931.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, 36.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 35.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 46.

- Berenstein, Rhona J. Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996) pg. 83.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 36.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 47.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. “Monster Culture (Seven These)” Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1996. Pg. 4.

Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet, pg. 86.

Cohen, “Monster Culture (Seven These)”, pg. 5-6.

Cohen, “Monster Culture (Seven These)”, pg. 5.

Hughs, “The taste of blood meant the end of aloneness”, pg. 143.