[Dracula] had also to have an erotic element about him (and not because he sank his teeth into women)…It’s a mysterious matter and has something to do with the physical appeal of the person who’s draining your life. It’s like being a sexual blood donor… Women are attracted to men for any of hundreds of reasons. One of them is a response to the demand to give oneself, and what greater evidence of giving is there than your blood flowing literally from your own bloodstream? It’s the complete abandonment of a woman to the power of a man.

Christopher Lee on playing Dracula

Though not the first vampire of the Gothic genre (that title belongs to John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819), ‘Varney the Vampyre’ in Varney (1845 to 1847), and Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872)), Dracula has maintained his hold in the public eye decades after the book’s publication by staking the desirous hearts (pun intended) of many people, especially heterosexual women.

Because Dracula was mentioned 60 times when respondents were asked to remember who their first monstrous attraction was, this week we’re going to take a peek at the hypnotic allure of Dracula and the history behind this mysterious, sepulchral (and sometimes cape-wearing) character within film and television, from Bela Lugosi, to Christopher Lee, to Gary Oldman.

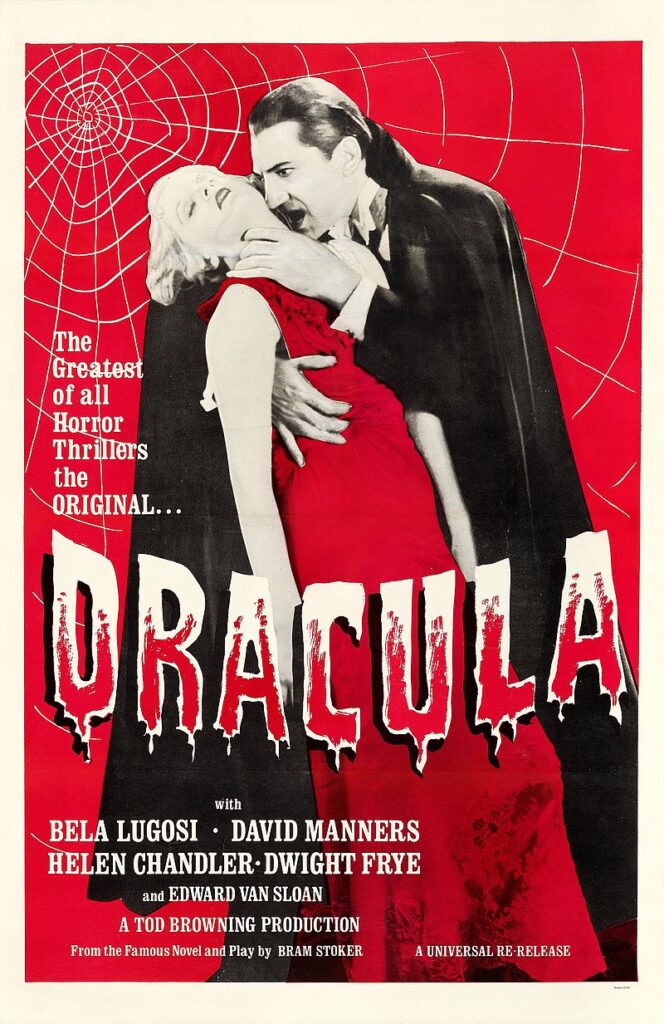

Let’s set the stage: It’s 1931 and Hollywood executives at Universal Pictures are worried.1 With just two months until the release of Dracula, starring the intense-gazed (and wildly underpaid) Bela Lugosi, Universal was uncertain if the movie was going to be successful due to its unprecedented thrill and supernatural elements that had only previously been seen by American audiences through the chiller movie The Cat and the Canary (1927). Prior to the Stock Market crash, the movie had initially been intended as a sprawling epic, adapted from Bram Stoker’s novel. However, with the Great Depression’s shadow lengthening to touch any and all industries, execs worried that the movie adaptation would flop and so swung into a different direction, hiring Hamilton Deane, who had already adapted the book into a play.

Though the movie was released prior to the Hays Code, the execs of Dracula perilously balanced between wanting to insert sensual tones into the movie to attract women to the film without being overt and explicit, and thus crossing over into being too suggestive. The inherently erotic subtext of vampire bites was broadly understood and recognized, so much so that Universal execs (unsuccessfully) fought against filming the scene in which Dracula attacks Renfield. The bite was perceived as queer, and so directors and writers were notified that “Dracula is only to attack women”. Furthermore, though bite marks would appear in the 1958 Dracula, starring Christopher Lee, Lugosi’s Dracula was not permitted to show the bite marks as it was deemed too suggestive.2

Dracula’s appearance drastically changed to be more alluring to general audiences as well. The 1922 German film Nosferatu portrayed the vampire as a grotesque creature, and even Stoker’s character (the source material!) vastly differed from what we associate Dracula with today: pale skin, dark hair, and altogether a “charming but deadly lover with hypnotic eyes”.3 Stoker’s Dracula, however, was an old man with “a long white mustache”4 who had a “lofty domed forehead, and hair growing scantily round the temples, but profusely elsewhere”, including the palms of his hands.5 Not so easy on the eyes. Yet it was Lugosi’s Dracula, and later Christopher Lee’s and Gary Oldman’s, that made his striking appearance so commonplace and recognizable.

Having pitched Dracula as a swoon-worthy character, Universal began to market the film as “The story of the strangest passion the world has ever known!” in the hopes that women would overlook the storyline of a blood-sucking vampire in lieu of a love story, even releasing the film on Valentine’s Day. A promotional poster for the movie printed in The Tyler-Courier Times in Tyler, Texas headlined the movie with “The Caress No Woman Can Resist!” (right). Universal’s marketing strategies—including publicity that audience members had fainted in horror while watching the movie—were a hit: Dracula, for all its gambles in sensuality and horror, made the largest profit of Universal’s 1931 releases, grossing $700,0006 and precipitating a boom of horror films during the 1930s.7

Lugosi would also become a sensational hit with Dracula’s popularity. Thrust into the spotlight, Lugosi was perceived with a complicated mixture of fear and attraction. In a Motion Picture Classic Magazine interview, Hungarian actor Lugosi explained his sensational appeal:

"When I was playing Dracula on the stage, my audiences were women. Women. There were men, too. Escorts the women had brought with them. For reasons only their dark subconscious knew. In order to establish a subtle sex intimacy. Contact. In order to cling to and feel the sensuous thrill of protection. Men did not come of their own volition. Women did. Came--and knew an ecstasy dragged from the depths of unspeakable things. Came--and then came back again. And again. Women wrote me letters. Ah, what letters women wrote me. Young girls. Women from 17-30. Letters of a horrible hunger. Asking me if I cared only for maidens' blood. Asking me if I had done the play because I was in reality that sort of Thing. and through these letters, couched in terms of shuddering, transparent fear, there ran the hideous note of hope. They hoped that I was Dracula. They hoped that my love was the love of--Dracula."8

Vampires were not new to cinema in 1931, however, it was Lugosi’s aristocratic charm and his conventionally attractive human exterior that concealed his evil supernatural identity that proved most influential to the genre for decades to come, especially erotically. The cape wasn’t the only thing that would be forever associated with Dracula because of Lugosi: the classic vampire would be defined by being “thoroughly evil, but by virtue of his powers—physical, mental and, by implication, sexual—he is able to captivate and control others, especially women.”9

Inherently, vampires are perhaps one of the most sexual monsters to exist within the monster pantheon: their need to drink blood puts them within intimate and close proximity with their victims, many of whom are more than willing to offer up their bodies for the creature. The vampire’s embrace is explicit in it’s taboo allure. Andrew Tudor perhaps bluntly summarizes it best:

"…the moment of bloodtaking has many of the external signs of the loving and erotic embrace. There is no need, therefore, to construct elaborate analogies between blood and semen, as do some psychoanalytic accounts, to establish the irreducibly sexual character of the vampire/victim relationship. Once given a presentably human figure as the vampire, demonstrating parallels with sexual activity does not require esoteric symbolic interpretations; it arises quite routinely from straightforward similarities in situation, posture, and action." 10

Though Dracula would pop up sporadically throughout the 1930s, 40s, and 50s in films such as the sequel Dracula’s Daughter (1936), Son of Dracula (1944), House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945), as well as various knock-offs that did not have the rights to Dracula’s outright image (including Bela Lugosi himself), the marriage of sensuality and horror as a marketing and artistic tactic would not be duplicated again until 1958 with Christopher Lee playing the titular role.11 Producer Anthony Hinds didn’t even consider other actors besides Christopher Lee as he was the perfect amalgamation of erotic, sympathetic, tragic, and romantic. As with Lugosi, execs wanted to woo women into theaters by using, as Tim Stanley synopsized, a subversive movie “that…hinted…women might quite like having their neck chewed on by a stud”.12 Amplifying the sensual and erotic tones, Director Terence Fisher even instructed actress Melissa Stribling during scenes in which Dracula bit Mina to “imagine [she was having] one whale of a sexual night, the one of [her] whole sexual experience” and that she needed to “Give [him] that in [her] face!”.13 The bliss and passion evident in the storyline and acting contributed to cementing Dracula as an erotic story, a legacy for which Fisher was deeply proud of: “My greatest contribution to the Dracula myth was to bring out the underlying sexual element of the in the story. He [Dracula] is basically sexual. At the moment he bites, it is the culmination of a sexual experience”.14

Even Christopher Lee understood the sensual and sympathetic ‘hero’ role he was to play as Dracula, a portrayal that was original and unconventional for its time. Says Lee: “I had perhaps discovered something in the character which other people hadn’t or hadn’t noticed or hadn’t decided to present, and that is that the character is heroic, erotic and romantic”.15 His motivation to portray Dracula as an unconventional hero was due to Lee’s melancholic interpretation of the Count, stating, “I’ve always tried to put an element of sadness, which I’ve termed the loneliness of evil, into his character. Dracula doesn’t want to live, but he’s got to! He doesn’t want to go on existing as the undead, but he has no choice”.16

Dracula 1958 UK Poster

This sympathy and romanticism signaled a shift in the monster zeitgeist and the public’s changing response to vampires specifically. Margaret Carter describes this shift as the creation of the “Sympathetic Vampire”, suggesting that while the 19th-century vampire “inspired sympathy despite its curse”, this would evolve within the late twentieth century to inspire sympathy for vampires “precisely because he or she is a vampire”.17 This cultural shift could have been bolstered by, as Christopher Frayling describes, the steady “domestication” of vampire stories, which separated the vampire from its medieval or classical settings and relegated it to the “present” or contemporary setting.18 The “domestication” of vampires produced a contradictory tension for Dracula as a figure: he had always stood as a metaphorical “threat to American domesticity”, yet, as Dracula developed into a more popular figure, he simultaneously was integrated within a “reassuring part of…domesticity”.19 This was notable as Dracula featured in more camp and kitsch-y media like American network television, which used horror figures like Dracula, Vampira, Ghoulardi, and Tarantula Ghoul as “horror hosts” that made “sardonic or sick jokes about the material to be shown”.20 By “defanging” Dracula, in a sense, and framing him within a comedy setting that not only brought him into everyday American households, but also reassured the American population through jokes about his macabre or threatening personality, Dracula as a figure distanced himself from Stoker’s alienating and fearsome conception. He was a character that the public could sympathize for or with, closing the gap between the monstrous “Other” that figures like Dracula embodied.

This doesn’t even touch the way 60s and 70s cinema was obsessed with the vampire, especially sexually, and how it produced a number of Dracula spin-off pornos with ground-breaking cinematic titles like: Dracula (the Dirty Old Man) (1969), Sex and the Single Vampire (1970), Dracula Sucks (Lust At First Bite) (1978), and, for posterity sake, I’ll include Kiss Me Quick! (1964) because it features Dracula even though its show-stopping plot is about an asexual alien ambassador from a distant planet who comes down to earth in search of feminine breeding stock.

Even the weird little guy that is Nosferatu got to have his sexualized time in the sun (well, maybe not sun…). Isabelle Adjani, the actress who played Lucy Westenra in Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (1979) described the erotic allure of Nosferatu to her character:

There's a sexual element. She is gradually attracted towards Nosferatu. She feels a fascination — as we all would, think. First, she hopes to save the people of the town by sacrificing herself. But then, there is a moment of transition. There is a scene when he is sucking her blood — sucking and sucking like an animal—and suddenly her face takes on a new expression, a sexual one, and she will not let him go away any more. There is a desire that has been born. A moment like this has never been seen in a vampire picture. 21

All of this laid the groundwork for Francis Ford Coppola and Gary Oldman in the three-time, Academy award-winning Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), in which Dracula is largely characterized as a sympathetic and tragic character, yearning to be reunited with his long-lost reincarnated lover, Mina. The tragedy and romanticism of Coppola’s Dracula was praised by Richard Nelson Corliss, an American film critic and magazine editor for Time, who wrote: “Coppola brings the old spook story alive…Everyone knows that Dracula has a heart; Coppola knows that it is more than an organ to drive a stake into. To the director, the count is a restless spirit who has been condemned for too many years to interment in cruddy movies. This luscious film restores the creature’s nobility and gives him peace”.22

Scene from Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) in which Jonathan Harker is being feasted upon by Dracula’s wives.

Scene from Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) in which Jonathan Harker is being feasted upon by Dracula’s wives.

Though at times he is portrayed as an old man, similar to the novel’s conception of Dracula, Oldman’s Dracula shifts from terrifying bat, to fearsome werewolf, to handsome and stylish gentleman in pursuit of Mina and her sexual innocence. The fluid nature of Oldman’s Dracula allowed for the proverbial “Monster Titillation Dial” to be cranked up, as it was no longer exciting enough to just show Dracula bite his victims to represent sensuality and eroticism (though the scene is still commonly referenced for its steaminess and seduction). The 1992 movie is the most erotically and romantically saturated interpretation of Dracula, at least explicitly, with Coppola himself describing the movie as “an erotic dream”.23 It is a “cornucopia of intertwined limbs, mouths and chests”, from Jonathan being hypnotized into a near orgy with Dracula’s harem of vampiric wives, to Dracula in wolf form drinking the blood of a writhing and ecstasy-overwhelmed Lucy, to Dracula and Mina professing their eternal devotion to one another during a blood drinking ritual.24 The characters, especially the human ones, are ensnared within the erotic monster’s grasp, with no sign of struggle. And why should they, when such a hold is conveyed often and repeatedly as sexual euphoria and freedom? Each bite and feast within Coppola’s movie is, as Fisher had illustrated 34-years previously with his own film, “the culmination of a sexual experience”.

It cannot be overstated Dracula’s influence on the vampire, especially the Sympathetic Vampire that became the prevailing figure in late 20th-century media, from Rice’s Louis de Pointe du Lac to Meyer’s Edward Cullen. Today, Dracula is still an ever present figure in movies, television, comics, and books. However, it is no wonder that he persists as a cultural figure when Dracula represented a threat to stifled and repressed sexuality within Victorian England, thus positioning himself as an embodiment of seduction and forbidden love/lust. For many heterosexual women, Dracula embodies excitement, thrill, and the promise of pleasure, an eroticism and romanticism so timeless his relevancy endures. It is as author Nina Auerbach, who had grown up during the 1950s, encapsulates: “Vampires were supposed to menace women, but to me at least, they promised protection against a destiny of girdles, spike heels, and approval”.25

References

- Gray, Tim. “A Valentine to 1931’s ‘Dracula’: Universal Touted Film as a Love Story”. Variety. 2nd February 2018. https://variety.com/2018/artisans/features/universal-1931-dracula-1202683151/

- Jordan, Waylon. “Celebrate 89 Years of ‘Dracula’ This Valentine’s Day!”. iHorror. 11th February 2020. https://ihorror.com/celebrate-89-years-of-dracula-this-valentines-day/

- Hutchings, Peter. “Dracula Lives!” in Dracula. London: I.B. Taurus, 2003. p. 21.

- Stoker, Bram. Dracula. p. 25

- Ibid. p. 28.

- Vieira, Mark A. Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003.

- Hutchings, Dracula, p. 21.

- Vieira, Hollywood Horror, p. 29.

- Tudor, Andrew. Monsters and Mad Scientists: A Cultural History of the Horror Movie. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989. p. 165

- Tudor, Monsters and Mad Scientists, 163.

- Hutchings, Dracula, p. 21-22.

- Stanley, Tim. “Why Christopher Lee’s Dracula Didn’t Suck”. The Telegraph. 29th September 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170929075343/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/film/what-to-watch/christopher-lee-dracula-movies-hammer/

- Dracula: A House That Hammer Built Special Magazine. Peveril Publishing, May 1998, p. 13.

- Berriman, Ian. “Dracula from the SFX Archives”. Gamesradar. 25th May 2013. https://www.gamesradar.com/dracula-from-the-sfx-archives/

- Miller, Mark A & David J. Hogan: Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing and Horror Cinema, 2nd ed. (2020)

- Flynn, John L. Cinematic vampires: the living dead on film and television. (1992) p.86.

- Carter, Margaret. “The Vampire as Alien in Contemporary Fiction” in J. Gordon and V. Hollinger (eds) Blood Read: the Vampire as Metaphor in Contemporary Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997).

- Frayling, Christopher. Vampyres. p. 64

- Hutchings, Dracula, p. 24.

- Ibid.

- Kennedy, Harlan. “Dracula is a Bourgeois Nightmare, Says Herzog”. The New York Times, 30 July 1978. https://www.nytimes.com/1978/07/30/archives/dracula-is-a-bourgeois-nightmare-says-herzog-bourgeois-nightmare.html

- Corliss, Richard. “A Vampire With Heart”. Time. 23 Nov. 1992. https://web.archive.org/web/20100812194852/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,977025,00.html

- Suton, Koraljka. “How Francis Ford Coppola Breathed New Life into ‘Bram Stoker’s Dracula”. Cinephilia & Beyond. https://cinephiliabeyond.org/dracula/

- Ibid.

- Auerbach, Nina. Our Vampires, Ourselves. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 1995, p. 4.