Part 1

[T]he secret of the power in their song: it is the sound of the subversive, luring us from the orderly conscious world down to the depth of the world of dreams, and the harder we try to ignore that singing, the more we desperately want to hear it.

—Meri Lao, Seduction and the Secret Power of Women: The Lure of Sirens and Mermaids

Ah, the mermaid. The mermaid is a timeless figure who still persists within our cultural imagination today: from Disney’s Little Mermaid (1989)—which grossed more than $6 million during its first week in theaters and is currently being remade into a live-action version—to Starbucks split-tail logo, she is an instantly recognizable creature from her long, flowing hair to her sparkling fishy tail.1 Our obsession with the mermaid has transplanted her firmly within lore globally; where there is a body of water—from rivers, to lakes, to lochs, to oceans—you can bet yourself that the locals within the region have one story or another about a beautiful and alluring fish-woman swimming in its depths.

As we continue forward during this glorious month of MerMay, we’ll examine the role of the mermaid and her siren call throughout both time and across the globe. Perhaps one of the oldest and most recognizable erotic monsters, the mermaid is a fascinating figure of paradox: she is both sexually tempestuous and unattainable; a symbol and provider of luck, as well as a harbinger of destruction. It’s for this reason that the Monstrous Desire Study rejoices as we continue to take a look at the mermaid and the eroticism that is inherent to her identity.

Who is the Mermaid Today?

long chain of references that have defined the mermaid as a locus of cultural meaning, [that] can be divided into three layers: 1) the feudal-popular-pagan traditional culture with its superstitious sailors and folk ballads with sea creatures, 2) the bourgeois-Christian culture to which to which both [Hans Christian] Anderson’s fairy tale and Erikson’s statue at Copenhagen’s harbor belong and 3) finally, mass culture with its multi-media exploitation of Anderson’s fairy tale, the most characteristic example of which is Disney’s postmodern musical animated film. 4

A (Not So) Brief History of the Mermaid

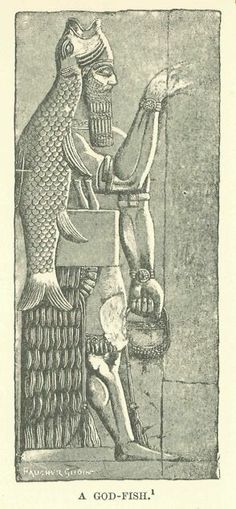

The Babylonians, in fact, were the first to create the earliest-known depiction of a mermaid via sealstones which they used to “sign” documents by pressing carved stone images into hot wax. One such 18th-century sealstone portrayed a half-human, half-fish creature, perhaps to represent Ea in his merman form.8

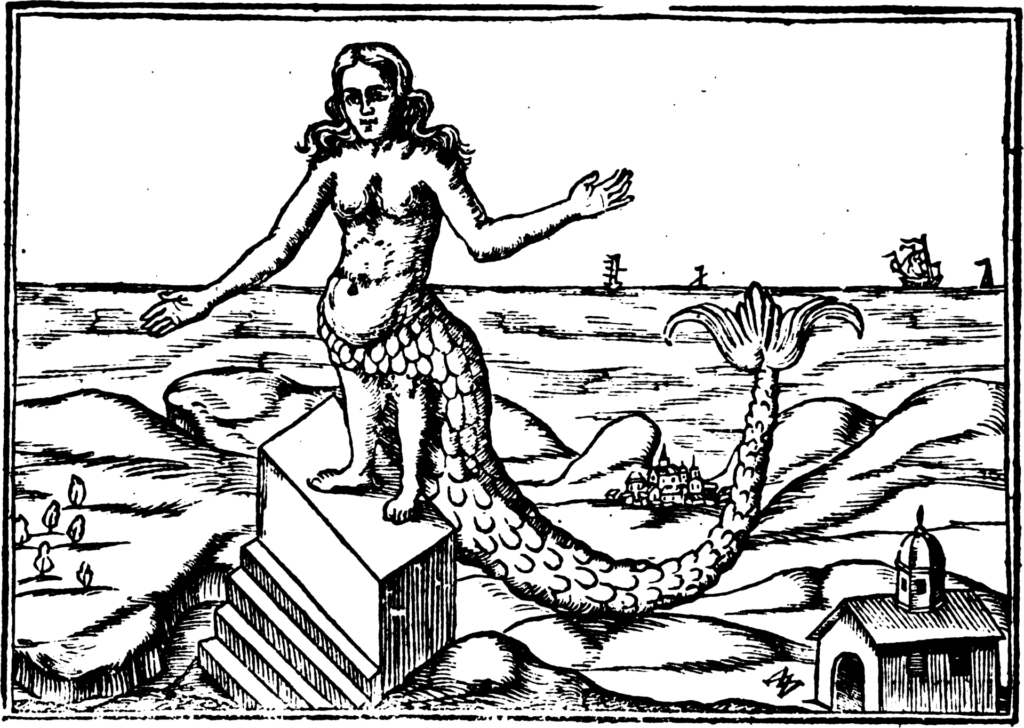

In Syria, the moon-goddess Atargatis’ entire body was that of a fish, except for her human head. Atargatis—also referred to as Derketo by the Greeks—dealt with all things fish: Syrians abstained from eating fish in her honor, and could not eat them without a license issued by the goddess herself (which helped priests within her temples produce a revenue).9 The glory of Atargatis would spread throughout Greece and Rome, and eventually, Europe and Britain via Roman conquest.

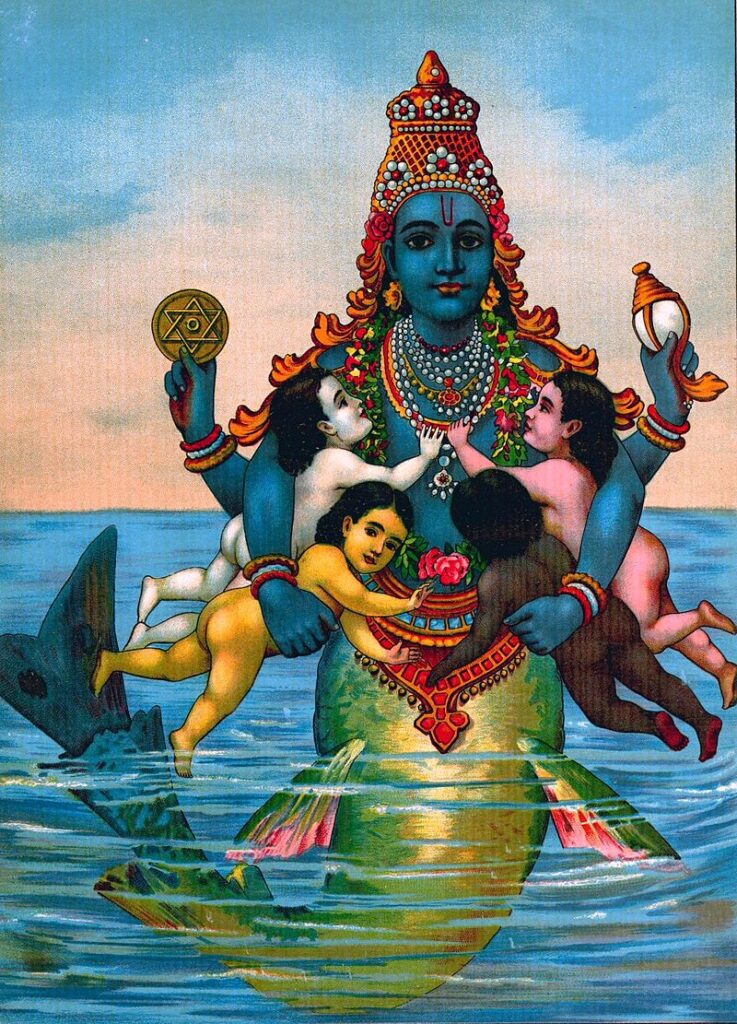

Matsya would not be the only mermaid interpretation within India, either. The Apsaras, or Apsarases, were celestial water-nymphs attached to the court of Indra, while the nagas/naginis—half-human, half-serpent nature spirits—lived at the bottom of lakes, rivers, and streams guarding treasures, sacred knowledge, and had the power to produce rain and floods.11

Like India, ancient Greece possessed their own slew of aquatic mythical creatures, from the innumerable water nymphs to water gods and goddesses to sirens. Ancient Greeks categorized their nymphs according to their environment:

- Oceanids lived in the oceans.

- Nereids resided in the seas and the foam along rocky coastlines.

- Naiads could be found in freshwater—lakes, rivers, and streams, marshes, and sometimes fountains.12

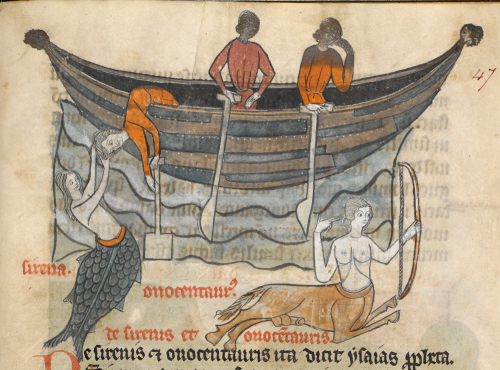

At the time of their introduction in Homer’s Odyssey, the sirens weren’t described as bird-like, but rather disembodied voices.

Their bird-like form materialized through Greek artists who portrayed the sirens as woman-faced birds. They were creatures with compelling and hypnotic voices that lured sailors to their deaths either by drowning or crashing their ships into rocks.

Even tall tales of Alexander the Great’s conquers often included encounters with dangerous but erotic mermaids. Though Alexander the Great died in 323 B.C., the early Christian Era “crystallized and circulated” stories about Alexander, especially those featuring mermaids.25 In one story, Alexander and his band of men stumbled across mermaids who set upon them. The story was illustrated in a Bodleian MS. (No. 264), The Romance of Alexander, portraying a mermaid drowning:

her soldier victim, upon whom she looks down with satisfaction. Another is dragging a soldier to her; unresisting, he kisses her. The third water-woman clutches a soldier’s cloak as he flees. The remaining two soldiers appear to have a chance of escape; one is on his knees. Alexander surveys the disturbing scene with uplifted hand and an expression of surprise.26

As the Age of Reason unfolds; as Britain and France battle for the mastery of an overseas empire; as Newton deduces the law of gravity; as Napoleon menaces the liberty of Europe, the interest of the common man in the marvellous [sic] and the mythical might be expected to diminish. But, as we shall see, reports of the mermaid’s appearances round our shores—made, in many cases, by sincere, honest eye-witnesses—aroused considerable interest whenever they appeared in the Press. Belief in the mermaid undoubtedly diminished considerably, but interest in her was unflagging. More faked mermaids were produced and exhibited than at any other period, and the mermaid herself remained a highly controversial figure throughout the nineteenth century.33

This is only a brief glimpse into the history of the mermaid and does not fully encapsulate her vibrant history, nor her various shared identities around the globe. The mermaid, sadly, cannot be done justice in a mere 5-6 pages (she is too larger than life for that!). Instead, the Monstrous Desire Study will attempt to explore the mermaid’s intrinsic sensuality now that I have contextualized the mermaid by skimming the surface of her history. In part 2, I will explore the mermaid further as an erotic symbol, especially in relation to her identity as a femme fatale archetype, and how eroticism is inherent to not only her identity, but largely shapes her physical configuration as well!

Works Cited

Skye Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore. Massachusetts: Adams Media, 2012. pg 7.

Gwen Benwell and Arthur Waugh. Sea Enchantress: The Tale of the Mermaid and her Kin. London: Hutchinson & Co., 1961. Pg. 13.

Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore, 24.

Finn Hauberg Mortensen. “The Little Mermaid: Icon and Disneyfication”. Scandinavian Studies, Winter 2008, Vol. 80, No. 4 (Winter 2008). pg. 442.

Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore, 24.

Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore, 137.

Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 23.

- Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore, 80.

Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 28.

- Carolyn Turgeon The Mermaid Handbook: An Alluring Treasury of Literature, Lore, Art, Recipes, and Projects. New York: Harper Design, 2018.

- Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore, 148.

- Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore, 17.

Ibid.

Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 39.

- Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore, 85.

- Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 36.

- Ibid.

Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 41.

- Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 43.

- Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 42.

Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 44.

Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 47.

- Ibid.

- Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 48.

- Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 52.

Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 54.

- Alexander, Mermaids: The Myths, Legends & Lore, 86.

- Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 69.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 72.

- Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 86.

- Benwell and Waugh, Sea Enchantress, 101.