Part 1

Content Warning: this essay contains descriptions and discussions of assault and rape, as well as explicitly sexual images.

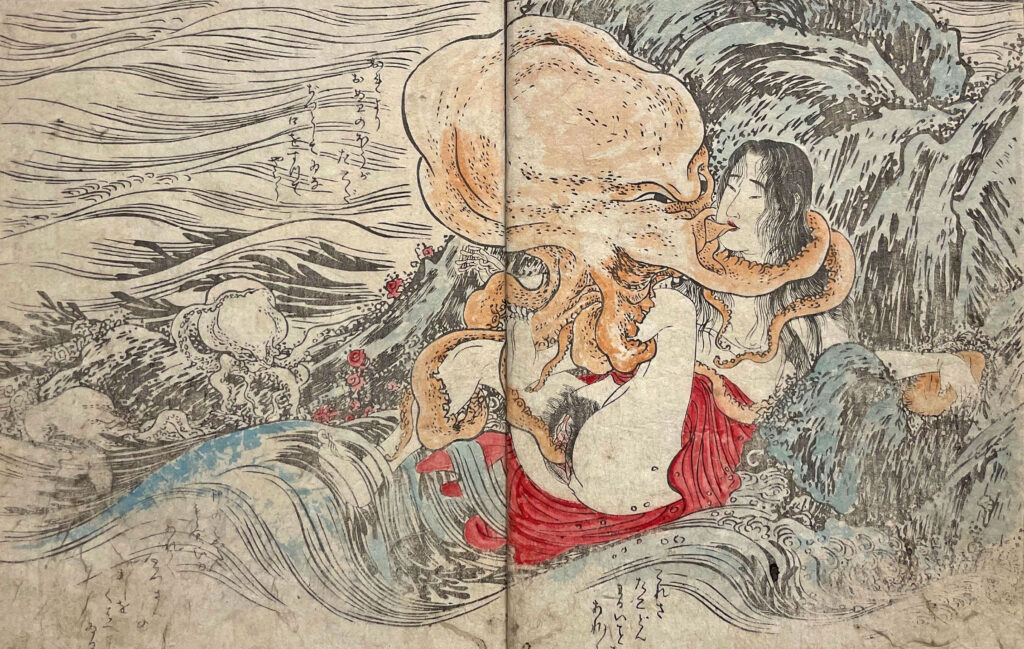

With its tentacles, the horrible beast sucks the tips of her breasts and rummages in her mouth, while its head drinks from her lower parts. The almost superhuman expression of agony and sorrow—which convulses this long, graceful female figure with aquiline nose—and the hysterical joy—which emanates at the same time from her forehead, from those eyes closed as in death—are admirable.

—French novelist Joris Karl Huysmans describing Hokusai's "Diver and Two Octopi"

Whether or not you consider yourself a monster fucker, or someone merely interested in the topic, you’ve probably heard of tentacle porn, or tentacle play. The genre has become increasingly more popular in Western media, finding itself at the forefront of many titillating popular monster romance novels like Katee Robert’s The Kraken’s Sacrifice or Lillian Lark’s Stalked by the Kraken. Yet, Western media’s fascination with erotic tentacle play is a newfound phenomenon, the genre having only been imported from Japan within the last few decades. Rather, the history of erotic tentacle play within Japan not only precedes contemporary manga, where the genre gained global significance, but can be traced through Japan’s art history as far back as the Edo-period. This week, the Monstrous Desire Study examines why we’re suckers (heh, get it? Suckers? Because tentacles have suckers?…Ahem. I’m done) for tentacles and their historical relevance within art history and culture!

What is Tentacle Play?

Tentacle play, also known as “tentacle rape”, conjures up images of great, writhing, lubricious tentacles that bind, squeeze, and penetrate a wriggling person who is, more often than not, a woman. Its definition, however, is as slippery as its content. Kimi Rito, author of The History of Hentai Manga: An Expressionist Examination of Eromanga characterizes modern-day tentacle play/rape as a genre that “usually involves a monster or mysterious life form with tentacles playing with a girl’s body, usually developing into a scene where said woman gets violated by those tentacles”.1 This definition, however, delineates tentacle play through the taboo of violation. Though Rito’s definition fittingly contextualizes tentacle play in eromanga, rape and violation do not always take place in tentacle play. In Katee Robert’s The Kraken’s Sacrifice, for example, the female protagonist is never violated by her demon-kraken lover; in fact, consent is emphasized repeatedly throughout the narrative and the use of tentacles for sexual pleasure is enthusiastically welcomed.2

Instead, I would like to tweak and build upon Rito’s definition to instead categorize tentacle play as not a woman being violated by tentacles, but rather, a person receiving pleasure from tentacles. This definition not only broadens tentacle play outside of the context of eromanga, but highlights the key differences in the evolution of the genre as it expanded to more global audiences. As such, I will oscillate between the terms “tentacle play” and “tentacle rape” to distinguish the difference’s within the genre concerning consensual sexual pleasure and rape. This is not to Other tentacle rape through an Orientalist gaze: rape-play does exist within Western erotic media, and is a popular trope within the erotica genre, especially within the sub-category of Dark Romance. Rather, the differentiation between “tentacle rape” and “tentacle play” is important when examining the genre’s shared attributes as well as their categorical deviations.

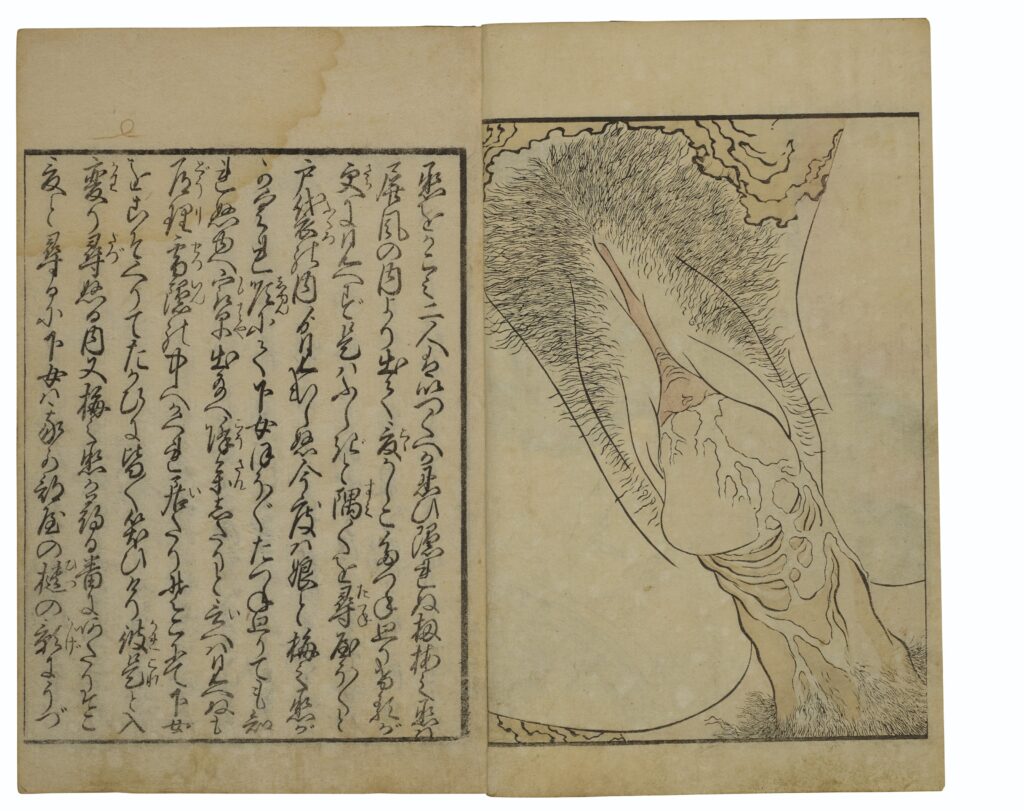

With that being said, when defining tentacle play, we cannot do so without first examining its role in eromanga, as well as its historical presence in Japan’s art history. Beloved tropes in eromanga, such as the “cross-section view”—or, an illustrated view of insertion during sex that helps visualize the hidden or inner workings for the audience—and close-ups, would not have the cultural relevance that they possess currently without the influence of art styles like shunga during the Edo-period.3 (Also, sidenote: this print is so surreal. A creampie? In my art history? It’s more likely than you think!)

By tracing the historical trajectory of Japanese art history, this not only helps to contextualize the framework through which eromanga’s tentacle play emerged from, but the three main conditions that Rito outlines to characterize tentacle play/rape:

- Regardless if it is a living organism or not, it will have long, narrow, sinuous limbs that can move freely.

- These limbs will work independently, as if having a will of their own, and the owner of these limbs can operate them from long distances.

- One can clearly tell that the woman (or sometimes, man) being attacked feels pleasure. The purpose of the attack is sexual assault, with the victim’s will being violated, and the reader can understand this clearly.4

The History of the Abalone Diver: Shunga and Tentacle Play

Much of Japan’s erotic art is motivated and shaped by censorship. Before the conception of eromanga, Japanese artists during the Edo-period (1615-1868)—also known as ukiyo-e artists—found their proverbial hands tied by visual art restrictions. Though printed materials were only a small portion of the crackdowns during each censorship period (the Kyōhō reforms of the 1720s, the Kansei reforms of the 1790s, and the Tempō reforms of the 1840s), this still included the visual arts. The censorship reforms banned all sexually explicit works, forcing sexually explicit books and prints to be published under pseudonyms or artist signature omission.5 It appears that the people of Japan—men and women, young and old, from a wide range of class statuses—were not going to let the restrictions inhibit either the production or acquisition of shunga, or, erotic woodprinting art. Scholars now speculate that the production and circulation of shunga was vast during the Edo-period, in spite of restrictions.6

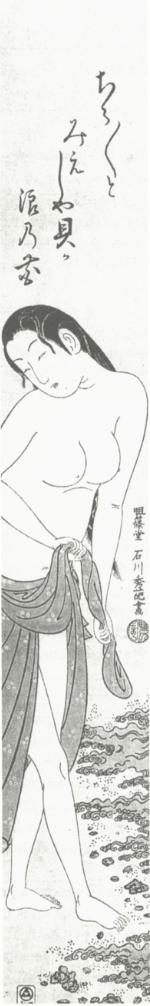

However, because of censorship, ukiyo-e artists needed to produce art that bypassed the restrictions. This art was called abuna-e, or, “risky pictures”.7 “Risky picture” subject material featured the oh so scandalous imagery of “women entering the bath, trimming their toe-nails, playing coquettishly with pets or small children, fighting a strong wind or engaging in any other activity that allowed for titillating glimpses of the female form”, including a popular theme of scantily-clothed, female abalone divers (ama) wringing out their wet skirts and showing tantalizing glimpses of skin.8

Ishikawa Toyonobu’s pillar print (seen right) is just one example of abuna-e. Specializing in painting beautiful women, Toyonobu’s pillar print, Diver (c. 1760), features just that: a beautiful, half-naked female diver wringing out the ends of her wet skirt. Her breasts exposed, the diver peers over her should, elongating her neck while her wet hair hangs down her back. Because of the narrow format of the print, the diver “dominates the image”.9 As she lifts her skirts to wring out seawater, the action exposes her long legs and just barely covers her genitalia, teasing the audience. Floating above her head reads a coy poem, its euphemism clear: “Flutteringly visible, a shell seems like a flower in the waves.”10

However, prior to Edo-period literature, female abalone divers were a romanticized—but not yet sexualized—figure in Japanese art and literature.11 The female diver was made widely popular through various iterations and variations of the famous ancient folklore Taishokan (“The Great Woven Cap”). Though its earliest version can be traced back to the 14-century, the story remained prominent and culturally relevant through Japanese art, ballads, plays, and poetry that retold and parodied the folklore centuries after its publication. So the dramatic story goes (in a very rough and short summary of the tale), a diving woman is tasked to retrieve a precious gem from the Dragon King of the Sea. The diver, however, is caught mid-heist after she snatches the gem and flees with the Dragon King’s guards hot on her tail. Upon realizing that she is incapable of out-swimming the guards, the diver cuts open her chest to hide the gem inside before she is pulled back up to the surface. In the end, the diver sacrifices herself so that she may deliver the gem to Kamatari, the guardian deity of the Fujiwara, who then places the gem in the forehead of the Buddha Sakyamuni in the Golden Hall at Kōfuku.12

The original folklore is “essentially a Buddhist moral tale”, and, as a result, does not contain sexual themes pertaining to the diving woman.13 Sexual elements of the tale would not develop explicitly until the Edo-period, during which time the tale was a common print theme parodied (mitate) not just amongst ukiyo-e artists, but also appeared as dramatic ballad-dramas (kōwaka-mai), dramatic chanting (jōruri), and theatrical Kabuki throughout the 15th to 19th century.14 Its evolution from Buddhist parable to sexual parody can be traced through its various iterations. Take, for example, the 18th-century interpretation painted by artist Okumura Masano. As Danielle Talerico observes, Masano’s painting of the tale, specifically the pursuit scene between the diver and the Dragon King’s guards, portrays the King’s attendants similarly to late seventeenth-century depictions, except for a “once human creature wearing an octopus on its head” which developed into “a warrior octopus with a humanoid body”.15 Masano’s octopus is not only purposefully anatomically inaccurate to emphasize expressiveness (the eyes and funnel of the octopus are repositioned to create more humanoid and recognized expressions), but it is the first variation of the tale in which the octopus and the diver are paired, a theme that would become prominent in future iterations of the tale in the 1700s.16

It is around this time, especially the late 18th-century, we begin to see artists sexualizing the diver. Talerico attributes this to a number of variables such as “ancient poetry dealing with the diver’s way of life; fourteenth-century Noh dramas featuring diving women; and sexually charged vocabulary of the Edo period all played a part in consolidating the notion of divers as objects of desire”.17 The culture at large would shift away from the romanticized interpretation of the diver and instead pivot towards not only sexualization, but conflating eroticism and sex with nearness to water/the ocean.18 This manifested itself in dual-meaning terminology and sly innuendo:

- Mizu shōbai (“water trade” or prostitution)

- Mizuage (sexual initiation)

- Mizushō (wanton woman)19

- Tako (term for “octopus” and popular slang for vagina during the Edo-period)20

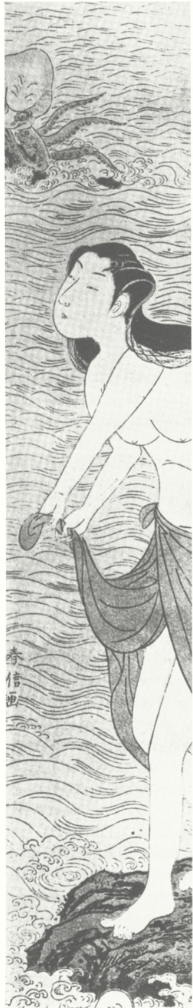

As such, the marriage of eroticism and the sea featured the ocean as an erotic site for many ukiyo-e artists, especially during the Edo-period. During this time frame, the female diver was not only sexualized, but her image was paired with erotic symbolism that aided in the eroticism of the art and bolstered the sexual nature of the figure. The octopus, while a euphemism for the vagina, began to be painted with sexual intent. In a pillar print done by an unnamed artist in the style of Suzuki Harunobu (seen right) (c. 1760), a half-naked diver is wringing out her skirts after she has left the ocean. Common enough setting and content for ukiyo-e art, however, there is a voyeur watching her: an octopus. The diver is unaware, but there in the background is an octopus heading towards her with “ill-intent”.21

Censorship pushed ukiyo-e artists to rely upon coy word and pun-play to emphasize the erotic subtext of their art. In Katsukawa Shunshō’s art titled Diver and Amorous Octopus (1773-4) (seen left), the abalone shell held in the hands of the half-naked female diver not-so-subtly refers to her vulva.22 Within the print, the female diver peers over her shoulder at an octopus with a furrowed brow and large eyes. Like Masano’s octopus, Shunshō’s creature possesses inaccurate octopus features so that it can express itself more clearly, which Talerico characterizes as “a look of consternation” that “suggests sexual tension”.23 It has a hold of her ankle with one tentacle while another reaches up underneath her skirt towards her hidden genitalia. The diver, however, does not appear troubled or scared; rather she seems rather unfazed by the octopus trying to keep her from truly leaving the ocean. From the held abalone—a Nara-period metaphor for vulvas, and thus a metaphor for the diver’s vulva—to the straining octopus tentacle, the sexual tension in the piece is provocative without being outright explicit, not in the same way like other artists such as Kitao Shigemasa.24

Censorship pushed ukiyo-e artists to rely upon coy word and pun-play to emphasize the erotic subtext of their art. In Katsukawa Shunshō’s art titled Diver and Amorous Octopus (1773-4) (seen left), the abalone shell held in the hands of the half-naked female diver not-so-subtly refers to her vulva.22 Within the print, the female diver peers over her shoulder at an octopus with a furrowed brow and large eyes. Like Masano’s octopus, Shunshō’s creature possesses inaccurate octopus features so that it can express itself more clearly, which Talerico characterizes as “a look of consternation” that “suggests sexual tension”.23 It has a hold of her ankle with one tentacle while another reaches up underneath her skirt towards her hidden genitalia. The diver, however, does not appear troubled or scared; rather she seems rather unfazed by the octopus trying to keep her from truly leaving the ocean. From the held abalone—a Nara-period metaphor for vulvas, and thus a metaphor for the diver’s vulva—to the straining octopus tentacle, the sexual tension in the piece is provocative without being outright explicit, not in the same way like other artists such as Kitao Shigemasa.24

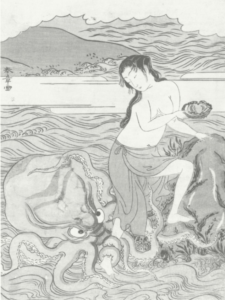

Kitao Shigemasa’s art would be the first of the Edo-period to explicitly portray a diver sexually entangled with an octopus.25 In his print, Parody of the Noh Drama (Ama) (1781) (seen above), the Tamatori folklore finds itself once again back in the spotlight as the print is a parody of the pursuit scene between the diver and the octopus guard. The diver and octopus are entwined in one another beneath the ocean waves while Kamatari and his retinue wait above the surface, unaware of what is happening beneath them. The diver is held splayed by the octopus, each limb held at bay with a tentacle, including one of her hands which clutches a weapon, either a sword or knife. The large octopus is, like most erotic portrayals of octopuses, inaccurate, however, Shigemasa’s interpretation finds itself uniquely different from all other ukiyo-e octopus portrayals: it has a penis. We can’t miss it: because the print is divided into two halves and takes up two pages, and the diver’s exposed and penetrated genitalia is nearly centered with the page seam, and thus the image as a whole. Text separates the two respective scenes of above and below sea, and parodies the Tamatori story by mixing both “the sacred with the secular”.26

Only five years later, ukiyo-e artist Katsukawa Shunshō (the very same artist who made The Diver and the Amorous Octopus!) produced yet another erotic painting between a woman and an octopus titled Lust of Many Women on One Thousand Nights (1786) (seen above), this one far more explicit than The Diver and the Amorous Octopus. Like Shigemasa, Shunshō’s print features a woman enveloped in an octopus’s hold. The large octopus’s tentacles are similarly wrapped around the woman’s ankles, holding her splayed for it as it penetrates her vagina with another tentacle, while another tentacle is wrapped around her neck, seemingly to hold her head up so that it can enter her mouth with its funnel. Her genitalia take center-stage of the print just the same as Shigemasa’s Parody of the Noh Drama. The pinkness of her vulva against the pale whiteness of her skin draws the audience’s eyes directly toward it, especially in contrast to the orange-red of the octopus, the vibrant red of her skirt, and the blue of the ocean. The octopus is, yet again, inaccurately drawn, however, this is not just to accomplish an emotive expression—such as the intense stare into the woman’s face—but to allow the octopus access to the woman’s mouth via its funnel. The funnel is erroneously placed between the octopuses’ eyes to mimic a mouth so that it may plunder the woman’s mouth, similar to a kiss.

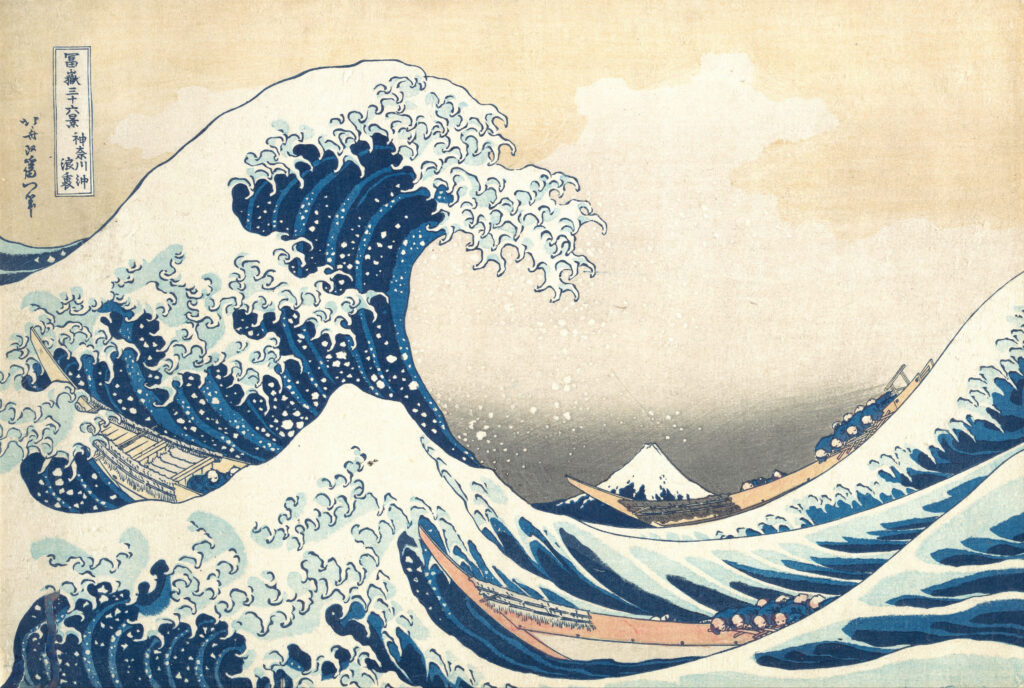

Katsushika Hokusai would also duplicate the use of the misplaced octopus funnel in his famous piece The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (1814) (seen above), also known as the Diver and the Two Octopi, from his three-volume erotic series Old True Sophisticates of the Club of Delightful Skills (Kinoe no Komatsu). You may be already familiar with Hokusai’s work: Hokusai is the artist behind the famous ukiyo-e print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831)(seen below)! However, more than 15-years before Hokusai would create the beautiful, Prussian-blue print of a far-off Mount Fuji and a tumultuous sea, Hokusai would be well known for his shunga prints. The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife is the last, well-known Edo-period shunga piece that portrays a diving woman and an octopus.27 According to Talerico, “it is the culmination of the history of Tamatori imagery that parodies the self-sacrificing virtue of the diving woman’s role.”28 Amidst a series of erotic prints of couples in various stages of intercourse, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife can be found in the third volume of Old True Sophisticates of the Club of Delightful Skills. The piece stands out in unique contrast to the rest of the prints, all of which portray human-and-human couplings. In The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, however, a female diver is caught in the throes of passion between two octopuses.

However, more than 15-years before Hokusai would create the beautiful, Prussian-blue print of a far-off Mount Fuji and a tumultuous sea, Hokusai would be well known for his shunga prints. The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife is the last, well-known Edo-period shunga piece that portrays a diving woman and an octopus.27 According to Talerico, “it is the culmination of the history of Tamatori imagery that parodies the self-sacrificing virtue of the diving woman’s role.”28 Amidst a series of erotic prints of couples in various stages of intercourse, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife can be found in the third volume of Old True Sophisticates of the Club of Delightful Skills. The piece stands out in unique contrast to the rest of the prints, all of which portray human-and-human couplings. In The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, however, a female diver is caught in the throes of passion between two octopuses.

The print is unique for many reasons, and not just for its human-octopus ménage-à-trois. Though many Western art historians have erroneously interpreted the scene to be one of violation or rape (Jack Hillier even described the piece as a “ghoulish print of a young woman being violated”) this appraisal is ignorant of the artistic imagery as well as the cultural references it is parodying.29 In the print, the naked diver reclines against algae-slick rocks, perhaps evocative of vulva slickness/lubrication stimulated through arousal. The sinuous lines of her body arch into the pleasure she receives between her widely-spread legs because of the large octopus who is practicing cunnilingus on the diver. Its improperly placed funnel acts as a mouth and stimulates both her vulva and clitoris. The large octopus’s tentacles are twined around her thighs while the diver grasps tightly onto its tentacles, not to push away, but to maintain. At her head, a smaller octopus—the son of the larger octopus—fondles her left nipple and holds her neck up to suck her mouth with its funnel.

Unlike his predecessors, Hokusai forgoes expressiveness in his octopuses to make them both accurate and inaccurate to accomplish different evocations. Though the funnel’s are inaccurately placed between the octopus’s eyes, they operate as mouths to give sole focus on the diver and her pleasure. However, their eyes are not human and expressive like other shunga octopus and instead “serve to dehumanize the octopi, heightening the foreign qualities of these strange and mysterious sea creatures and reinforcing the exoticism/eroticism of the act”.30

Scrolling text surrounding the imagery further supports that the scene is one of pleasure and not violation:

[Octopus:] Wondering when, when to do the abduction, but today is the day. At last she’s captured. Even so, this is a plump, good pussy. Even a greater delicacy than a potato. Saa, saa, sucking, sucking, sucking to complete satisfaction, then to take her to be imprisoned in the Dragon King’s palace. Zufu, zufu, zufu, Chu! Chu! Chu! Chu! Zu! Zu!

[Diver:] That hateful octopus fu, fu, fu, fu… rather aa, aa. . .sucking on the surface of the inner mouth of my womb until I’m breathless, aa, eee, I’m coming! By that projecting mouth. By that projecting mouth the open vagina is teased. Oh! What to do? Yoo, oo, oo, oo, hoo, aa, that, oo, good, good, oo, good, good, haa, good, fu, fu, fu, fuu, fuu. Again! Yoo, yoo, yoo, yoo. Until now although people have called me aa, fu, fu, fu, fuu, fuu, fuu… octopus! Octopus! Oo, fu, fuu, fuu.

[Octopus:] Zuu, zuu, zuu, zuu, hicha-hicha, gucha-gucha, jutsu, chu, chu, chu, chu, guu, guu, zuu, zuu.

[Diver:] Say! How about, how about the feeling of being entwined by eight legs? Oh, oh, it’s swelling inside, aa, aa.

[Commentary:] Juices are flowing like hot water. Nura, mura, nura, doku, doku, doku.

[Diver:] Ee, moo, I’m becoming ticklish. One after another until I lose track fu, fu, fu, fuu, fuu, limits and boundaries are gone oo, oo, oo, I’ve arrived anna, aaaaaa, there, there, here, here, uu, mu, mu, mu, fun, mufu, umu, uuuuu, good! Good!

[Small Octopus:] After my parent is finished, I, too, will use my projecting mouth to rub from her clit to her ass until [she] loses consciousness, [and] when she revives,

I’ll do it again, chu, chu.31

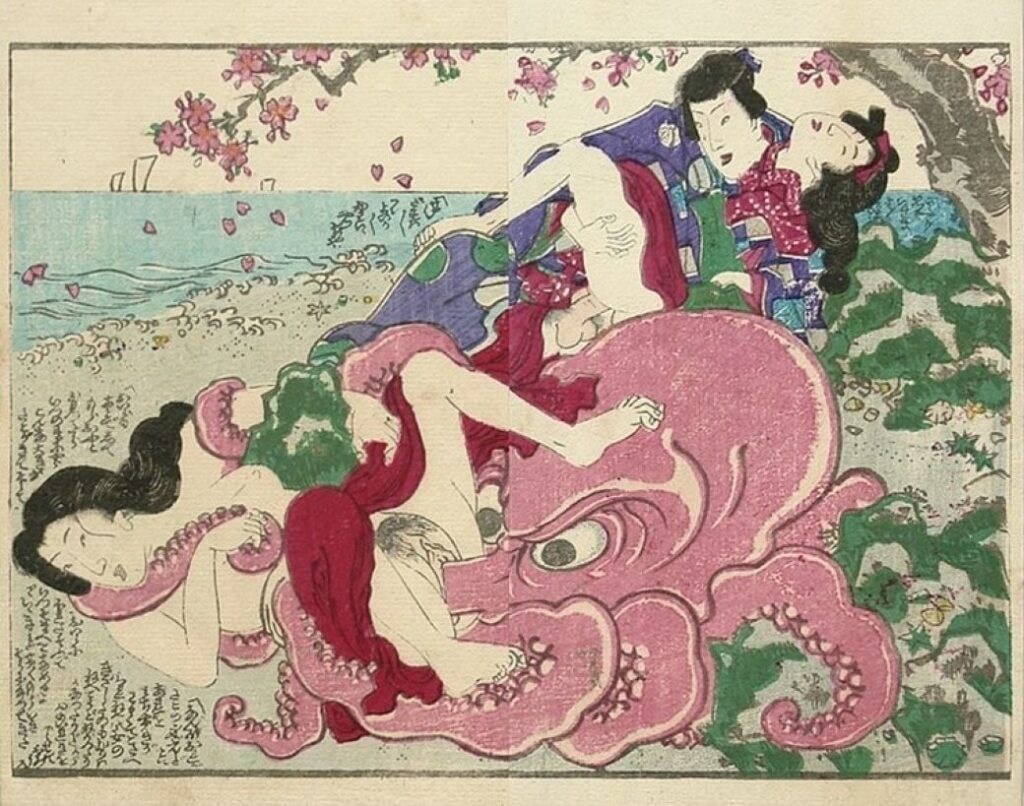

Completely detached from and ignorant to both the language and cultural references within the piece, Western art historians wrongly cast the scene as one of violation, however, Hokusai’s audience would have very likely recognized not only the print’s cultural reference to Tamatori because of its popularity, but acknowledge the parody it was as well. Though Hokusai’s Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife would be the last well-known Edo-period shunga piece that portrays a diving woman and an octopus, with other smaller or unnamed artists taking inspiration from Hokusai and other famous ukiyo-e artists (as seen below), it would not be the last time that themes concerning women, sexual pleasure, and tentacle creatures appeared within Japanese art and culture. Far from it, in fact. Rather, shunga and tentacle play would mark only the beginning of a long history of erotic tentacle art in Japan, and later, the world.

Works Cited

- Kimi Rito, The History of Hentai Manga: An Expressionist Examination of Eromanga. Portland: Denpa Books, 2021. Pg. 134.

- Katee Roberts. The Kraken’s Sacrifice. Trinkets and Tales LLC, 2022.

- Rito, The History of Hentai Manga, pg. 5.

- Rito, The History of Hentai Manga, pg. 135.

- Danielle Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints: A Fresh Approach to Hokusai’s “Diver and Two Octopi” in Impressions, No. 23 (2001), pg. 32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42597891

- Monta Hayakawa and C. Andrew Gerstle, “Who Were the Audiences for “Shunga?” in Japan Review, No. 26 (2013), pg. 17-18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41959815

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 32.

- Ibid.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 33.

- Translated by Danielle Talerico with the assistance of Professor Berry, Galen Lowe and Izumi Lowe.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 31-32.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 26-29.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 26.

- Ibid.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 30.

- Ibid.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 31.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 32.

- Ibid.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 34.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 33.

- Martinez, “The Ama: Tradition and Change,” 212; and Shibata, Seigo jiten, 26.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 33.

- Martinez, “The Ama: Tradition and Change,” 212; and Shibata, Seigo jiten, 26.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 34.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jack Hillier, The Art of Hokusai in Book Illustration. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. pg. 170.

- Talerico, “Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints”, pg. 36.

- Translated by Danielle Talerico with the assistance of Professor Berry and Hiroko Sakurai and based on transcriptions from Fukuda Kazuhiko, Ukiyoe no miwaku (The allure of ukiyo-e) (Tokyo: Kawade shobō shinsha, 1986), 179; Katsushika Hokusai, Kinoe no komatsu, 85 – 86; and Yasuda Yoshiaki and Sano Bunsai, Hokusai in Edo o yomu, vol. 1 (Tokyo: Futami shobō shinsha, 1996), 68-6.