Part 1

Woah, here she comes

(Watch out boy she's gonna chew you up) Watch out boy she's gonna chew you up (Woah, here she comes) She only come out at night Well she's a really hungry type (Woah, here she comes) Oh, the woman is wild, woman is wild No, I seen her here before Woah, woah, say (Woah, woah, oh woah) You gotta think about it She's a maneater, yeahHall & Oates

(It was a genuine struggle to choose between Hall & Oates “Maneater” and Nelly Furtado’s “Maneater”, I can’t lie.)

I am absolutely ecstatic to talk about the monstrous feminine. So far in this study, I’ve examined predominately male monsters (minus my beloved sirens and mermaids), but now we’re finally getting to the good stuff: the femme fatales, the she-demons, the, well, man-eaters.

Femme Castrator, or, the Vagina Dentata

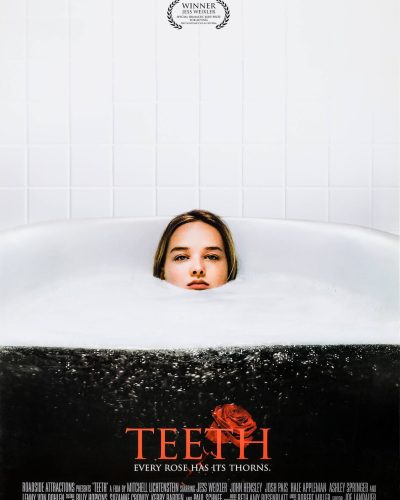

When the movie Teeth (2007) first came out, it lingered in the cultural atmosphere for years afterward like pure fear aerosolized. The shock and sensationalism it produced amongst young boys translated into giggled, nervous jokes about being careful while screwing girls, or else…

Too young to really grasp the movie’s intent or references, I had thought it grotesque. Who could ever come up with something so…weird? Teeth in a vagina? It caused a major eye-roll for me as a teenager, even years later. Because of course heterosexual men (to my presumption, at the time) would make up something so dehumanizing; that the source of their fear was rooted in something that they now couldn’t fuck or else be mutilated.

Funnily enough, Freud—the neurotic, coke-addicted, egomaniacal psychologist, you know the guy (Jesus I made him sound so much cooler than he actually was)—would actually agree with teenage-me (to an extent). His theorization on what is officially called the vagina dentata is at its core (ahem) a reflection of men’s fears and phantasies pertaining to castration and mutilation. As Barbara Creed eloquently puts it, the vagina dentata “is the mouth of hell” that “points to the duplicitous nature of woman, who promises paradise in order to ensnare her victims”.1 The vagina dentata is the femme castratrice who will swallow you up and annihilate you. It is perhaps, at its most surface level analysis, a demonstration of “women’s dangerous propensities for threatening men’s self-control, autonomy, and power”, a reflection of the gendering of the grotesque.2

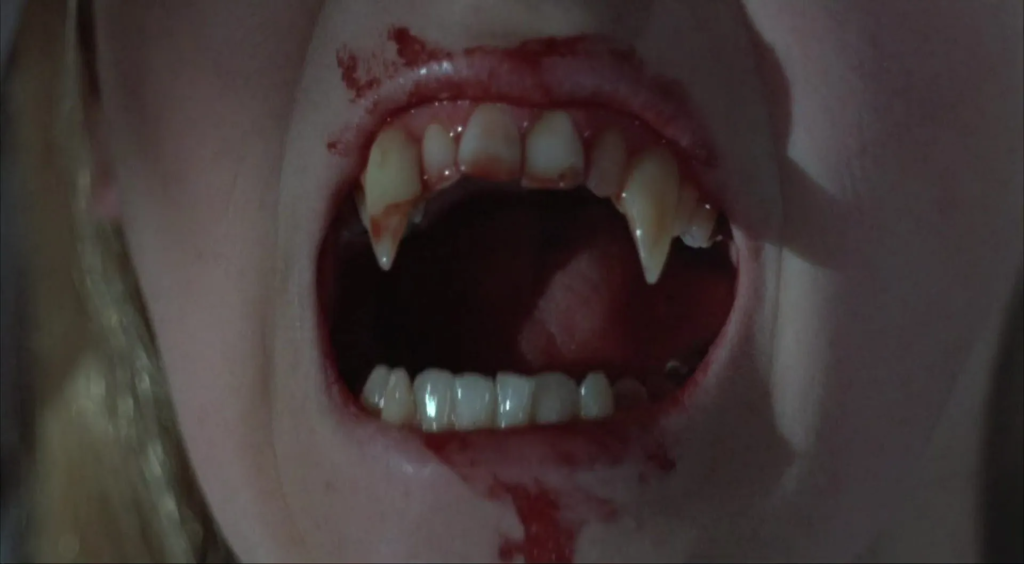

Despite how surreal and kooky it all sounds, like something Jordan B. Peterson would make up and cry about on some guy’s podcast, it still sounds all too familiar, doesn’t it? Not the toothy, maw genitalia—but the cultural relevance of the monstrous feminine creature, the femme fatale, who lures hapless male victims in with her beauty and sexuality only to devour them or lead them to their doom. Suddenly, all sorts of famous monsters spring to mind, both ancient and contemporary: beautiful Scylla, her lower body consisting of snapping hell-hounds and the tail of a fish; sirens & mermaids, tricking sailors to crash into the rocks and drown; female vampires hypnotizing their victims before taking a bite.

Amongst the Indigenous peoples of North America, there are at least 30 references to the vagina dentata.7 In fact, the first time the vagina dentata motif was noted occurred in 1895 by ethnologist Franz Boas who was working on North American tales (although the OED claims it was actually anthropologist Robert Lowie in 1908 in an article on Native American rituals and stories published in the Journal of American Folklore).8,9 The Ponca and Otoe tribes, for example, tell the tale of the trickster Coyote who is invited to spend the night between two beautiful but supposedly man-eating sisters with toothed vaginas. It is revealed that the young women had been cursed by a witch who had given them their vagina teeth. Coyote kills the eldest sister when she attempts to bite him with her vagina and knocks out all the teeth in the younger sister’s vagina except for one, “leaving just one blunt tooth that was very thrilling when making love.”10

For many North American Indigenous peoples, their legends include the vagina dentata motif, like the legend of the meat-eating fish that lives in the vagina of the Terrible Mother, or the motif is preceded by stories about passage through a dangerous door.11,12 One such tale concerning maiming doors that heroes must pass through is attested to amongst the Tsilhqotʼin, Shuswap, and Nlakaʼpamux people in which four heroes are stuck inside a house after the stone door slams shuts; they are only saved by the quick thinking of one brother who jams the door with a stick, but loses his small finger in the process.13 A Bella Coola indigenous tale portrays a house whose door is guarded by a fierce dog and the door closes “like jaws” once the hero passes through.14

Amongst other indigenous people, especially Inuit, dog heads are yet another common motif to demonstrate the genitals of the vagina dentata, similar to that of Scylla. The Chukchi in Siberia tell a story about a woman who has “something within her body gnawing its teeth like a dog” and later compares her vagina to the mouth of a wolf,15 and people within Tasiilaq, Greenland have a tale about the murderous Nalikateq who possesses a dog head hanging between her legs.16

Elsewhere in the world, the vagina dentata takes the form of other animals: it’s a serpent—or an eel, in places where there are no snakes—waiting in the lurk and ready to bite. In Polynesia, on the Tuamotus Islands, a woman named Faumea possessed eels in her vagina that killed all men who tried to sleep with her, but she teaches the hero of the story Tagaroa how to lure them outside so that he may sleep with her safely.17

Even simple fairy tales like that of Sleeping Beauty can be in some way interpreted as the vagina dentata: suitors must pass through a hedge of thorns to get to Sleeping Beauty, however, they are pierced by the bracket. Yet it is the prince who inspires love in her that is allowed safely through because it becomes “nothing but large beautiful flowers, which parted from each other of their own accord and let him pass unhurt”.18 Which feels rather…unambiguous in its metaphor.

To this day, the cultural prevalence of the vagina dentata can still be traced not just in our media, where it is a prevailing iconographic theme within horror movies like Jennifer’s Body, Alien, and any movie dealing with female vampirism (see: The Hunger), but also reflective within popular derogatory language for women or epithets for vaginas: ‘Man-eater’, ‘castrating bitch’, ‘man trap’, ‘bottomless pit’, ‘viper’, ‘snapper’, ‘vamp’, ‘dumb glutton’, ‘snatch’, and ‘dickmuncher’.19, 20

There is endless source material on the existence of the vagina dentata and its cultural ramification and influences, but for the sake of (delusional) brevity of this blog post and topic, I will simply focus on how it is a persistent motif within horror media (one could even argue that the chomping kraken from Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest is nothing more than a reflection of the ‘primordial cunt’, which gives a whole new meaning to all that goop it spits up on Jack Sparrow before devouring him). We’ll be looking at women’s role in the horror film in relation to her archetypes as not just the castrator, but simultaneously, the vampire and possessed woman as well (as outlined by author Barbara Creed). From lesbian vampires to succubus, I’m here to talk about the monstrous women who devour their prey.

Femmes and Fangs: Lesbian Vampires in Film

The vampire enfolds the victim in an apparent or real erotic embrace…She embraces her female victims, using all the power of her seductive wiles to soothe and placate anxieties before striking. The female vampire’s seduction exploits images of lesbian desire.23

One of my first blog posts was about the erotic influences of Dracula, specifically Bela Lugosi’s 1931 version, on vampires in cinema. Lugosi’s Dracula, with his captivating powers and aristocratic charm, hypnotized audiences with “their own suppressed desires for sensuality, for excitement and for immortality…[threatening them] through [their] own weaknesses.”24 This obsession with all things vampires would fulminate in the 60s and 70s, oversaturating the market with not just Dracula spin-offs, but movies concerning other vampire characters like Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla or the 16th century historical figure Elizabeth Bathory (who wasn’t quite a vampire, but we’ll get to that yet). Think you’re tired of yet another Marvel movie release? Almost half of the supernatural movies during the 70s focused on vampirism of some kind, “a proportion unmatched in any other period”.25

Though not overly common, female vampires in cinema weren’t a new thing: the earliest cinematic portrayal of a female vampire was Carl Theodore Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932), which was a loose adaptation of Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, followed a handful of years later by Dracula’s Daughter (1936). While Dreyer’s Vampyr expunged from its narrative any implication of sexuality, especially that of lesbianism, Dracula’s Daughter included a “muted lesbian encounter between a reluctant vampire-woman and a servant girl”.26 This category of film would base themselves off of two main sources: Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla or the 16th century Hungarian aristocrat Elizabeth Bathory,27 who was accused of (allegedly) systematically kidnapping, torturing, and murdering young women and bathing in their blood to maintain her youth and beauty (though there is a lot of back and forth amongst historians if these allegations were true or not). Though not a vampire herself, the Bathory case inspired a slew of vampiric media: some like Raymond T. McNally in his book Dracula was a Woman even theorized that Bram Stoker’s Dracula was based on Bathory herself as Stoker’s unpublished papers were chalk full of notes on the Elisabeth Bathory case.28

I cannot stress just how many female (lesbian) vampire movies came about during the 1970s. To demonstrate (and this does not even include all of the ground-breaking films):

- The Vampire Lovers (1970)

- La Noche de Walpurgis (1970)(released first in Spain)

- La Frisson des Vampires (1970)(released first in France)

- Vampyros Lesbos (1971)

- Daughters of Darkness (1971)

- Lust for a Vampire (1971)

- The Werewolf vs. the Vampire Woman (1971)(second release in US)

- Twins of Evil (1971)

- The Velvet Vampire (1971)

- The Blood Spattered bride (1972)

- The Nude Vampire (1972)

- Shadow of the Werewolf (1973)

- Blood Ceremony (1973)

- Immoral Tales (1973)*

- The Devil’s Plaything (1974)

- Lips of Blood (1975)

- Vampyres (1975)

- The Shiver of the Vampires (1975)(second release in US)

- Vampire Hookers (1978)

*(participation trophy for including a scene of Elizabeth Bathory)

For whatever reason, 1971 seemed to be an especially busy year for lesbian vampire movie makers. With titles like Vampyros Lesbos, who wouldn’t be excited?

Suddenly, the implicit sexuality of vampirism that was kept subtextual due to censorship laws (dictated by the Hayes Code until 1968) was made blatant through the female vampire narrative. Across the board, cinema during the 70s was marked by an increased portrayal of sex; this was no different in horror because the genre allowed for the depiction of “nudity, blood, and sexual titillation in a “safe” fantasy structure”.31 Freed from the constraints of previous censorship rules, filmmakers jumped at first opportunity to capitalize on pornography, conflating the female lesbian vampire with insatiable and predatory sexual lust. The female-vampiric horror genre was defined by lesbophobic and misogynistic stereotypes: lesbians as narcissists capable only of loving those that look like them; lesbianism as sterile and morbid; lesbians as sexual predators who woo hapless and innocent women away from the safety of heterosexuality with her wealth and supernatural powers.32 For example, the same company that created Christopher Lee’s Dracula (Hammer Films) also created the erotic, Carmilla trilogy: The Vampire Lovers (1970), Lust for a Vampire (1971) and Twins of Evil (1971). Hammer’s Karnstein trilogy was no different than any of the other female-vampiric movies of its decade: “unrelenting in their insistence upon sexual display, not merely in frequent female nudity but also in blurring the boundary between their predator’s sexual and vampiric predilections”.33

So where exactly did this explosive obsession with all things lesbian vampires come from? There are academics like Tudor who indicate that the lesbian vampire stood as “sexual symbolism”, or, emblematic iconography that embodied festering, reactionary cultural unrest at the time.34 The women’s liberation movement was occurring simultaneously as these films’ were being produced and released. With the emergence of second-wave feminism, the public (and especially the press) maligned and skewered the movement, giving ground to fears around a more aggressive—what many within hegemonic heterosexuality would demonize as predatory—expression of female sexuality.35** Though sexually-forward women had been derogatorily referred to as vampires as early as 1911 (“vamp”, to be precise, which referred to women who intentionally attracted and exploited men),36 the conflation of predatory vampirism with lesbianism and sexual freedom demonstrated a fundamental male fear: fear of being replaced, of the destruction of hegemonic heterosexuality, that male supremacy was actively being threatened.37 While vampires are inherently sexual, no matter their gender, it was female vampires that challenged the realm of acceptable feminine behavior; in the minds of misogynists, there was perhaps no difference between that of a blood-sucking, sexually-predatory creature of the night and the feminists who were routinely vilified by society at large, including by popular press. As James Craig Holte states simply, “Monsters are created out of perceived threats to patriarchal order.”38

There is a kernel of truth even in the seething accusation of hateful misogynists: queerness is threatening to heterosexuality, and the liberation of gender-oppressed people, especially for queer women, is through the destruction of patriarchy and the regimes that uphold it, including heterosexuality. Both positions of ‘lesbian’ and ‘female vampire’ are inherently political as they are dual figures perceived and represented by popular culture as sexually aggressive. It is for this reason that the female vampire is doubly monstrous: to use her seductive wiles on women marks her as queer, and “threatens to undermine the formal and highly symbolic relations of men and women essential to the continuation of patriarchal society”.39 Time and time again, the horror film grapples with patriarchal anxieties surrounding gender roles, the nuclear family, and heterosexual relations between men and women. The lesbian vampire is that which will not only woo women away from their “proper gender roles”, but will replace men entirely as once bitten “the victim is never shy…she happily joins her female seducer, lost to the real world forever”.40 The power, the fear behind female vampires, is that she disrupts identity and order and that her lust for both sex and blood means that “she does not respect the dictates of the law which set down the rules of proper sexual conduct”.41 It is for these crimes that they are always destroyed at the end of the films.

While the lesbian vampire genre of the 60s and 70s was not radical, nor did it challenge the gender basis inherent within the structures of heterosexuality, she would later be reimagined and reconfigured throughout the 1980s and beyond in films like The Hunger, starring Catherine Deneuve and Susan Sarandon. However, at this point in cinema, the female vampire and all her complexities faded from the forefront of the horror genre. For author Bonnie Zimmerman, the sapphic vampire’s exit from screen was because “men do not want to see themselves as victims, but the perpetrators of sexual violence: they want to see women subdued and violated by men, not other women”. For Zimmerman, the lesbian vampires presence in 70s horror was fetishistic in a way that positioned the lesbian vampire as something to be objectified, a sexual thrill that would always be in the end destroyed. I question the truth of that necessarily and if it is reflective of the current culture at large, however, I cannot renounce it entirely as the female vampire has not returned to the screen as enthusiastically as she did during the 70s (for better or worse).

There’s so much to talk about in reference to the lesbian vampire and how her image, though largely lesbophobic and misogynistic in her media origin, can be further reimagined and reinterpreted because of her inherently political ontology, however, we’d be here all day. Instead, in part 2 we will discuss the other monstrous-feminine archetype: the possessed woman, and how the cult classic Jennifer’s Body is an amalgamation of different monstrous-feminine bodies eager to swallow us up.

Footnotes

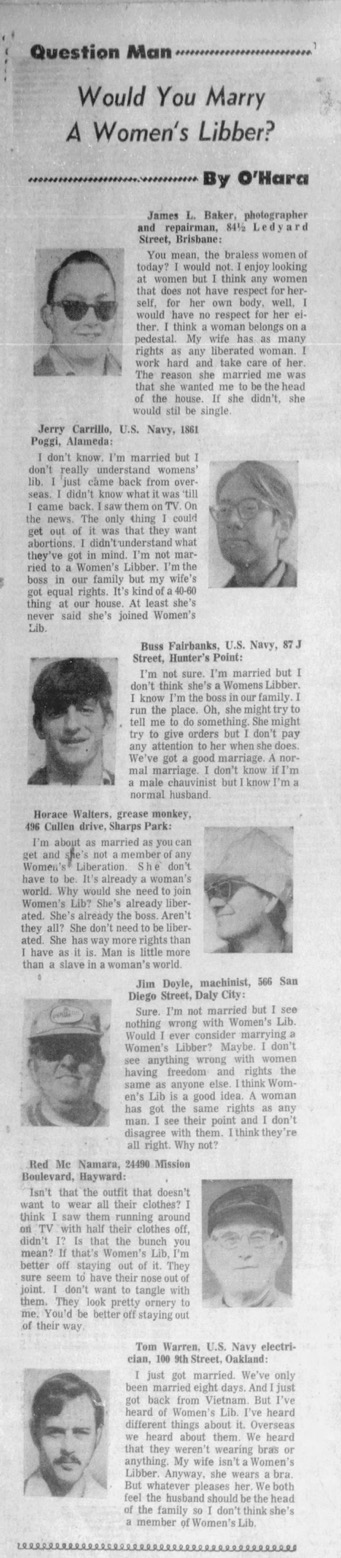

**As a side detour, I wanted to include a newspaper clipping I found on Twitter from 1971 that asked various men, “Would You Marry a Women’s Libber?” to demonstrate just how not normal men were about feminism during the time:

Out of the seven men, the only normal response is perhaps Jim Doyle. I love the delusion of Horace Walters, however, who believes its a woman’s world, baby, and we just live in it (derogatory) and the utter confusion of Tom Warren, who thinks the movement was about if women should wear bras. I assume all the wives were very happy in their relationships with these very normal, well-adjusted men (excluding you, Jim Doyle)!

Works Cited

- Creed, Barbara. The Monstrous Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. London & New York: Routledge, 1993. 432

- Miles, R. Margaret. “Carnal Abominations: The Female Body as Grotesque” in James Luther Adams and Wilson Yates (eds), The Grotesque in Art and Literature: Theological Reflections. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1997. p. 97

- Neumann, Erich. The Great Mother: An analysis of the Archetype, trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton, NJ: Princeton university Press. p 174.

- Monaghan, Patricia. The Book of Goddesses and Heroines. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1990

- Lederer, Wolfgang. “Snapping Teeth” in The Fear of Women. New York: Harvest, 1968. pg. 45

- Walker, Barbara. The Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1983. pg. 1034

- Thompson, Sith. Tales of the North American Indians. Cambridge, Harvard University Press 1929.

- Hopmann, Marianne Govers. “Scylla as a femme fatale” in Scylla: Myth, Metaphor, Paradox. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. p 139.

- Rees, Emma. The Vagina: A Literary and Cultural History. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. pg. 61

- Bastian, Elaine Dawn and Judy Mitchell. “Teeth in the Wrong Places” in Handbook of Native American Mythology. Santa Barbara: Bloomsbury Academic, 2004. pg. 81

- Neumann. The Great Mother. p 168.

- Hopmann. Scylla: Myth, Metaphor, Paradox. p 139.

- Gessian, Robert. “‘Vagina dentata’ dans la clinique et la mythologie”, La Psychanalyse 3: 1957. pg 287

- Ibid, 290

- Ibid, 178-9

- Ibid, 280

- Beckwith, Martha. Hawaiian Mythology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1940. pg. 289

- Grimm’s Fairy Tales. New York: Pantheon, 1944. p. 240.

- Creed. The Monstrous Feminine. 258

- Rees. The Vagina. 96

- Creed. The Monstrous Feminine. 435

- Ibid, 250

- Ibid.

- Tudor, Andrew. Monsters and Mad Scientists: A Cultural History of the Horror Movie. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell Ltd, 1989. pg 165

- Tudor, Monsters and Mad Scientists, 63-64

- Zimmerman, Bonnie. “Daughters of Darkness: the Lesbian Vampire on Film” in Barry Keith Grant, eg. Planks of Reason: Essays on the Horror Film, 154.

- Ursini, James and Alain Silver. The Vampire Film: From Nosferatu to Interview with the Vampire. New York: Limelight Editions, 1997.

- McNally, Raymond T. Dracula Was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania. McGraw-Hill, 1987.

- Zimmerman. “Daughters of Darkness: the Lesbian Vampire on Film”, 154.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Zimmerman. “Daughters of Darkness: the Lesbian Vampire on Film”, 155.

- Tudor, Monsters and Mad Scientists, 64.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “vamp (n.4),” July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/8649825895.

- Zimmerman. “Daughters of Darkness: the Lesbian Vampire on Film”, 156.

- Holte, James Craig. “Not All Fangs Are Phallic: Female film Vampires” in the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, 1999, Vol 10, No. 2 (38), A Century of Draculas. p. 164

- Creed. The Monstrous Feminine. 255.

- Ibid, 257.

- Ibid, 257-258.